How to deal with the bleakness of times

A three-pronged approach to doing our best in a meaningless and largely hostile universe

Perhaps the most optimistic statement about progress in human history articulated in recent times comes out of two books by Steven Pinker: The Better Angels of Our Nature and Enlightenment Now. The problem is that Pinker is not a historian, and both books have been heavily criticized by professional historians on methodological and factual grounds.

But what you are about to read is not an essay about Pinker’s optimism, or how misguided it may be. Even if he is right, the best one can conclude is that some countries during the 21st century are among the best places to live when it comes to human flourishing. Which is certainly not nothing! However, it doesn’t follow that (i) we could and ought to do much better, given the resources at our disposal; and (ii) it is more than possible, if not outright likely, that things will get worse pretty soon, either because we can’t bring ourselves to do something serious about climate change, or because some idiot will finally start a nuclear conflict, or simply because illiberalism and autocracy are on the rise. (See my recent essay on “Orwell: 2+2=5.”)

In other words, I think there is good philosophical and empirical ground for being pessimists about human nature. Philosophical pessimism is not committed to the strong notion that there has not been or there never will be moral progress (scientific and technological progress is a different beast, and is obviously undeniable). The stance only implies that there is no historical necessity demanding such progress, that advances may just as well be followed by setbacks, and that there is no grand overarching narrative at play, religious (e.g., Christianity) or secular (e.g., Marxism, or neoliberalism). Moreover, the philosophical pessimist rejects any talk of cosmic meaning, maintaining instead that meaning is local and provisional, the result of individual and collective human thought and nothing else.

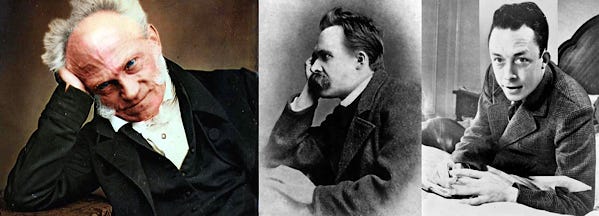

Given the above, how do we respond constructively to whatever bleakness we may perceive in the current historical and political moment? (If you do not perceive any such bleakness, I suggest you get a better pair of critical thinking glasses.) My colleague Joshua Dienstag, author of Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit, summarizes three classes of reactions that he associates with three of the major pessimists in recent history: Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Albert Camus. In what follows I am going to describe aspects of each of these three recipes to deal with the Abyss, so to speak, suggesting that they are eminently complementary and that together they represent arguably the best response that reasonable and caring people can muster to whatever is going on in the world.

[If you are wondering how the suggestions below may or may not be compatible with Greco-Roman approaches like my two favorite, Stoicism and Skepticism, I think they are, but that’s a much larger project toward which for now I will just vaguely gesture.]

1. Temporary withdrawal into aesthetic contemplation (Schopenhauer)

One thing we can do when we feel overwhelmed by doomscrolling is to find refuge in aesthetic contemplation, a suggestion made by Arthur Schopenhauer. While Schopie meant such a withdrawal to be as complete and permanent as possible, here I am moderating his stance and suggest we do this every time we need to recharge our emotional and intellectual batteries. Which may be often, depending on how challenging the external circumstances are.

Schopenhauer proposed several aesthetic activities as a means to cope with the suffering inherent in human existence. He believed that engaging in these activities allowed individuals to at least temporarily escape the painful realities of life and find solace in beauty. Schopie regarded art to be a way to transcend the relentless desires and suffering that characterize human life.

Schopenhauer thought of music as the highest form of art. He believed that it communicates universal truths and emotions, transcending rational thought and allowing listeners to connect with the essence of life. For him, music serves as a direct reflection of the will, providing a unique means of escape. Personally, I don’t believe that music is in the truth business, but I do think that at an emotional level there are very few experiences available to humanity that are comparable to listening to great music. (Nope, I’m not going to get dragged into a discussion of what “great” means here!)

Schopie also recommended the visual arts: he rightly saw painting and sculpture as highly valuable aesthetic pursuits. Engaging with visual art allows us to experience beauty and contemplation, again helping us to distract ourselves from the suffering inherent in everyday life.

Finally, literature: reading literature enables us to explore different perspectives on existence, offering general insight while relieving personal suffering. Schopenhauer valued especially works that reflect the human condition, enabling readers to engage with the philosophical themes of life and suffering.

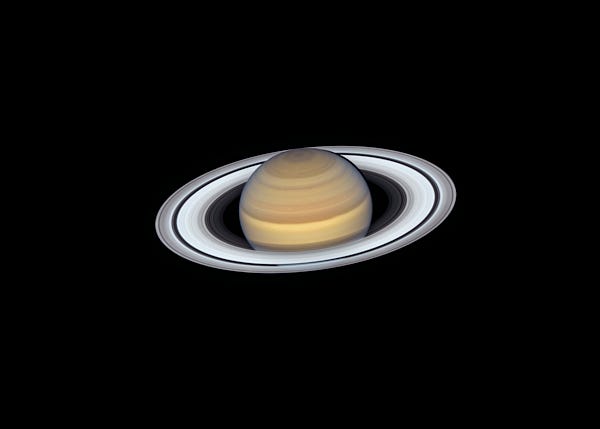

But I think there is more, much more, to a broad notion of aesthetic experience. Science, for instance, can be an invaluable source of aesthetic appreciation. I still remember vividly, for instance, the first time I looked through a small telescope to see Saturn’s rings. There they were, unaccountably suspended in space, surrounding the giant gaseous planet, absolutely beautiful. I was eight or nine years old when that happened, and images of planets, nebulas, and galaxies still very much have the same effect on me.

Whatever your favorite kind of aesthetic retreat, go there as often as you need, so long as you don’t make Schopenhauer’s mistake and confuse a temporary refuge for the whole solution to the problem. After you feel reinvigorated, come back out into the world and resume the fight.

2. Dionysian affirmation and creative will (Nietzsche)

Which brings me to our second approach to constructively handling the Abyss: Nietzsche’s notion of what he referred to as a “Dionysian” affirmation of our will.

Famously, Nietzsche drew a distinction between two aspects of human experience, which he termed Apollonian and Dionysian. The Apollonian is characterized by order, rationality, and individualism. It emphasizes clarity, restraint, and harmony and is symbolized by the Greek god Apollo. In contrast, the Dionysian drive embodies chaos, passion, and the primal aspects of human nature. It is associated with the god Dionysus and celebrates instinct, emotional expression, and the ecstasy of life. Nietzsche believed that the tension between these two drives is essential for creating profound art and meaningful experiences, but there is no reason to limit such analysis to art and not expand it instead to all aspects of living a meaningful life. A balance between the Apollonian and Dionysian, then, allows for a fuller expression of life, combining structure and chaos for a richer understanding of existence.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Figs in Winter: a Community of Reason to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.