What, if any, is the difference between religion and philosophy?

Turns out there is one, but it’s not what you may think

I am a philosopher. And I am not a religious person. These two sentences imply that philosophy is distinct from religion, and yet many would object, including a number of philosophers. I’ve given this issue much thought and have arrived at the conclusion that there is, indeed, a continuity, but also at least one fundamental difference between the two. And that difference has—perhaps surprisingly—nothing to do with gods.

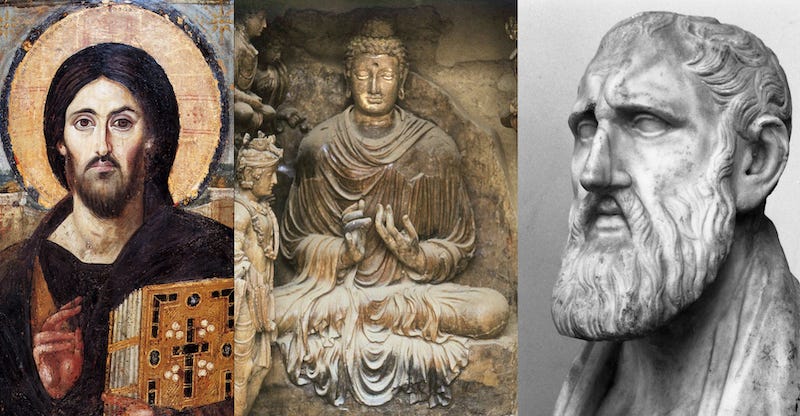

For the purposes of this discussion, let us compare three religions/philosophies: Christianity, Buddhism, and Stoicism. I picked these three because most people would agree that Christianity is clearly a religion, that just as clearly Stoicism is a philosophy, and that Buddhism falls somewhere in between. However, nothing important hinges on my specific choice, and the reader is welcome to repeat the exercise by swapping one or more of the candidates in this list for other examples of religions/philosophies.

In the introduction to a book that I co-edited with my colleagues Skye Cleary and Dan Kauffman, How to Live a Good Life—A Guide to Choosing Your Personal Philosophy of Life, I suggested that both religions and philosophies have three common elements: a metaphysics (i.e., an account of how the world hangs together), an ethics (i.e., an account of how we should behave in the world), and a set of practices. The following table should make clear what I mean, though the entries within each cell are meant to be illustrative, not exhaustive:

One thing should be obvious from the table: presence or absence of gods (and other supernatural entities or phenomena) is not what distinguishes religions from philosophies, despite the fact that I bet most people would consider that to be the demarcating criterion.

This is made even more clear if we keep going and add additional comparisons. Some versions of Buddhism are atheistic or otherwise secular. The same goes for non-pantheistic Stoicism. Moreover, Epicureanism includes a deist view of the supernatural, Platonism also had a god, and at least some versions of Taoism do too. Then again, there are both religions and philosophies that lack gods: Ethical Culture is an example of the first one, Confucianism of the second one. Believe it or not, there is even such a thing as Christian Atheism.

So clearly belief in gods does not provide us with a line separating religions and philosophies. And yet, the existence of such a line is strongly defended by many. Throughout the Middle Ages, for instance, philosophy has been considered the “handmaiden” of theology, a phrase introduced by one of the early Church Fathers, Clement of Alexandria (150–215 CE). Something similar was true for various strands of Medieval Islamic philosophy.

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) famously argued that “the book of Nature,” which is properly studied by philosophy (and, in modern times, science) cannot contradict revealed scriptures. However, since philosophical (and scientific) inquiry is a human activity and scripture is the direct word of God, if we ever find apparent contradictions between the two clearly theology overrides philosophy.

And therein lies the difference: in philosophy the human mind is the only available arbiter of truth or plausibility, there are no external source of revelation. In religion human truths are seen as fallible (which they are) and therefore secondary (which they are not, since they are the only game in town).

But, one might reasonably object, isn’t theology just a type of philosophical inquiry anyway? Not really. There certainly are similarities between the two. When theologians engage in apologetics, that is, in a defense of their religious beliefs, they do so by way of logical argumentation, just like philosophers do. And just as in philosophy, one’s argument always begin with a set of assumptions or axioms that are taken for granted and get the reasoning going.

Yet, there is a major difference: the starting points of a piece of philosophical reasoning are always, at least potentially, open to question. They are accepted only provisionally, literally for the sake of argument. Accordingly, there are two standard ways to counter an argument in philosophy: to show that it is invalid, meaning that something went wrong in the structure of the argument, so that the conclusions do not, in fact, follow from the premises; or to show that it is unsound, meaning that one or more of the premises ought to be rejected.

The second avenue (questioning soundness) is unavailable in theological debates. Christian theologians, for instance, can (more or less) freely debate the nature of the Trinity, but definitely not that god is, somehow, both One and Three. The penalty for doing so may be excommunication (or, in earlier times, being burnt at the stakes).

Compare this with the possibility that, as a Stoic, I disagree with Epictetus. In chapter 6 of my How to Be a Stoic I do just that: I question the ancient Stoic use of a design argument to infer that the cosmos is providential. Having done so, I have not been kicked off any Stoic Church, nor have I been branded as a heretic. (Though, naturally, people have disagreed with me on the topic.)

Another way to frame the distinction I’m trying to make is that—ideally, at least—philosophical inquiry is open ended. Just as in science, the inquirer strives to boldly go wherever reason and evidence lead. In the case of theology, by contrast, the conclusion is pre-determined and cannot possibly be contradicted by any argument or evidence.

Yet another way to put it may be this: philosophers are in the business of forming beliefs that are, as David Hume famously put it, proportional to the evidence. For a theologian, the evidence is relevant when it confirms faith, but has to be questioned or discarded when it doesn’t.

ὦ θεοί! I feel like the television broke, or the film jammed in the sprockets. You really got going there. I was engrossed chomping on popcorn and the episode ended with a major plot twist.

What happens next? You can write a book on this. Very insightful. 😊

My pet theory of religion is that it is a means of inducing an 'endorphin' high. Do something slightly painful for a long time and the endorphins, etc. kick in and you feel 'God', grace or enlightenment. At least in Zen while there are some silly stories (and some funny ones too) belief is not a big deal.

Sharing in the 'high' may have some utility in terms of group solidarity.

Sit in an uncomfortable posture ('just sitting') for a long time, trying to solve an impossible riddle while someone occasionally wacks ypu with a board...ah!

I do agree that dogma is a typical difference between religions and philosophy, but like all definitions the boundaries are fuzzy.