What counts as “evidence”?

From Sherlock Holmes to Bayes’s theorem: A guide to believing the right things

David Hume, the brilliant 18th century Scottish philosopher, and one of my personal favorites, famously said that:

“In our reasonings concerning matter of fact, there are all imaginable degrees of assurance, from the highest certainty to the lowest species of moral evidence. A wise man, therefore, proportions his belief to the evidence.” (Of Miracles; Part I.87)

Let me unpack the quote carefully, because there is a lot going on there. First, le Bon David, as he was known in French Enlightenment circles, specifically says that what he is about to assert pertains to “reasonings concerning matter of fact,” meaning statements people make about physical reality. He is not talking about assertions in mathematics or logic, for instance. Nor is he talking about literature or art.

Second, Hume states that in such matters there are “all imaginable degrees of assurance,” i.e., one can have varying degrees of confidence about one’s statements (about the world). For instance, I can say that I am somewhat (but, alas, not too much!) confident that AS Roma will win the Serie A championship this year; or that I am very confident that it will be hot and humid in Rome come August; or that I am close to certainty that Saturn has rings. This way of calibrating statements according to the perceived degree of their likelihood goes back to the ancient Academic Skeptics – particularly Carneades of Cyrene and Marcus Tullius Cicero – which is not surprising given that Hume considered himself their intellectual descendant.

Third, and this is the kicker, David concludes that a wise person (and don’t we all wish to be wise?) ought to proportion their beliefs to the available evidence, as much as it is possible. In other words, we are counseled to adopt a position that in modern epistemology is known as probabilism, and that is often couched in terms of Bayes’s theorem: we make an initial assessment of the likelihood that a certain statement about reality is true, then we keep “updating our priors,” as the technical jargon puts it, i.e., we revise our initial assessment up or down as a function of whether new evidence increases or decreases the probability of the truth of the statement in question.

As I’ve pointed out elsewhere, Hume’s sentence in his essay on miracles is the source of Carl Sagan’s famous “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” which is a logical special case of Hume’s general dictum.

[The phrase was actually not Sagan’s, as it was originally proposed by Marcello Truzzi, one of the co-founders of the Committee for the Scientific Investigations of Claims of the Paranormal, or CSICOP, nowadays known as the Committee on Scientific Inquiry, CSI. But Sagan is the one that popularized the notion to the wider public.]

All of the above, I think, makes eminent sense, and describes the way most of us actually behave in our daily lives. Whenever we need to make a decision on an important or complex issue, we gather evidence and we strive to arrive at the best possible decision.

But there is a hidden problem in Hume’s dictum: what, exactly, is “evidence”? For instance, when I write about one of my pet peeves, that many metaphysicians make all sorts of claims that I think are not even wrong, I make that claim because I think said metaphysicians do not provide any evidence, thus giving us no reason to believe their conclusions. But during one of these discussions here at Figs in Winter, a reader pointed out that I seemed to be using “evidence” as a synonym for “empirical data,” which is problematic because not all kinds of evidence are, in fact, empirical. Indeed, sometimes empirical evidence is simply not germane at all, for instance if we are concerned with a mathematical theorem. And the very fact that sometimes I use the phrase “empirical evidence” implies that there is such a thing as non-empirical evidence, otherwise the qualifier would be redundant. So, what’s going on?

Broadly speaking, the distinction between empirical evidence and other kinds of evidence hinges on the source of the data. Empirical evidence is based on information gathered through systematic observations or experimentation, whereas other kinds of evidence are based on reasoning, authority, or personal experience.

In this context, empirical evidence (from the Greek empeiria, meaning “experience”) is information acquired directly or indirectly through sensory experience (for instance, by way of instrumentation) that results in a systematic collection of data. This kind of evidence can be measured, recorded, and verified by others. It can be used to test a given hypothesis and can potentially prove it wrong. Moreover, the same experiment or sets of observations, when conducted again under similar conditions, should yield the same or similar results. Examples include measuring the growth rate of a plant over time, analyzing survey responses from a randomized population sample, or observing the spectral lines of a distant galaxy.

Non-empirical evidence, by contrast, generally relies on logic, abstract thought, existing knowledge, or personal accounts, rather than systematically newly collected data. The main types include:

Logical/Rational Evidence is derived from reasoning and deductive principles, where a conclusion is necessarily true if the premises are true. Possible sources are abstract principles, mathematical laws, or accepted definitions, and its applications include formal logic, mathematics, and philosophical arguments. For example: a proof in geometry (e.g., proving the Pythagorean theorem a^2 + b^2 = c^2) is based on logical evidence. The conclusion follows from the axioms, not a measurement of triangles in the real world.

Anecdotal Evidence can take the form of a personal story, a single case, or casual observation. The source is individual testimony, word-of-mouth, or memory. This kind of evidence is highly susceptible to cognitive biases and memory errors, and is not representative of a larger group or necessarily consistent with reality. It is, accordingly, considered the weakest form of evidence in both scientific and legal contexts, though it is extremely popular with politicians, purveyors of pseudoscience, and during conversations at the bar or at holiday dinners. For instance, a person claiming a certain supplement cured their illness because they felt better after taking it (an instance of the post hoc ergo propter hoc logical fallacy).

Authoritative Evidence is based on the opinion, testimony, or writings of an expert or recognized authority in a specific field. Sources include established texts, expert witnesses, or consensus among specialists. While highly valued, its strength depends entirely on the expert’s credentials, integrity, and whether their opinion is itself supported by strong empirical data or logically cogent arguments. For example: a doctor testifying in court about the cause of a patient’s injury, or a historian citing a recognized historical text.

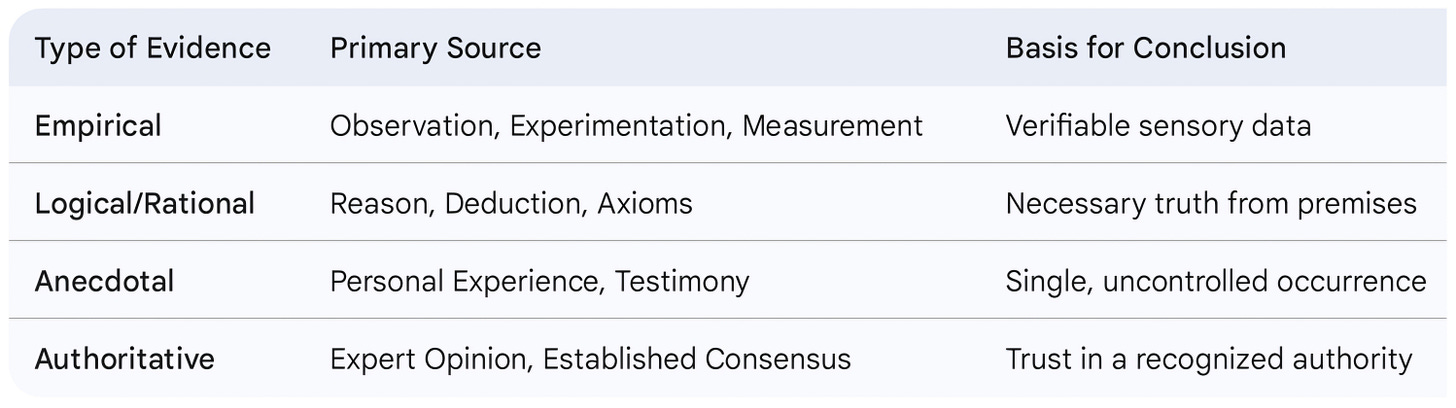

Here is a handy-dandy little table to keep the above differences in mind:

What are we to make of all of the above? At the end of the day, it seems to me, there are only two kinds of reliable evidence: empirical or logical, because authoritative evidence collapses into either of those two categories, and anecdotal evidence is simply not reliable, though it may be indicative of something that might be worth further investigated, again by way of empirical means.

Logic and math work on the basis of logical evidence, while science requires a combination of logical and empirical evidence, as empirical evidence by itself is rarely, if ever, conducive to generalizations about how the world works, given that such generalizations take the form of hypotheses and theories, which means of logical constructs.

What about philosophy? In my department at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center the joke is that the quickest way to end a philosophical conversation is to say something along the lines of “well, that’s an empirical question.” This is a grave mistake, as pointed out by philosophers from Aristotle to W.V.O. Quine. Philosophy is in the business of making sense of the broad canvass of the world by drawing on other disciplines, which means that it cannot afford to ignore empirical evidence, and therefore science. When it does so, it risks fulfilling Hume’s biting criticism of his own discipline:

“Generally speaking, the errors of philosophy are [not dangerous], only ridiculous.” (A Treatise of Human Understanding, 1.4.7)

Although I certainly appreciate that the article explains that there are other kinds of evidence than empirical, there is also an implied reductionist argument that at the very least I find unhelpful. There is no doubt to any reasonable person that empirical evidence has expanded human knowledge exponentially. But there is also a lack of recognition of what we have lost in abandoning a more holistic approach that split disciplines into neat categories.

There are many other forms of evidence. Cumulative evidence arising from aggregation or, although maybe weak on its own, argumentum ex silentio. There is also coherence evidence, which may be evidentially relevant and contextual evidence where background knowledge constrains plausibility independently of new data. Comparative or pattern evidence is absent. Historical evidence is reduced to authority when it is far more than that. Even modal considerations can add evidential force to explanations. Abductive reasoning is more than Bayesian updating and has its own evidential mode.

Science has replaced philosophy as the dominant authority on truth. Yet science is not oriented towards wisdom. The universal approach sought understanding that informed how to live. Science only shows how explain or manipulate. We seem to have gained precision and vast amounts of knowledge but to do what with? We seem to have lost integration, any sense of necessity and more importantly any shared account of why any of it matters. This is probably why we see the world on such a destructive path. We blind our understanding by granting authority to science without bounds, instead of recognising it as the remarkable tool that it is, rather than as a source of human meaning.

Excellent article. A lost opportunity of sorts for the french, they should have called him " David Humaine" .