Some times it’s a good idea to pause and reflect on the big picture. You know, something along the lines of Socrates’s famous “the unexamined life is not worth living.” Take literally, the Socratic injunction may be excessive, but I would argue that the occasionally examined life is lived better.

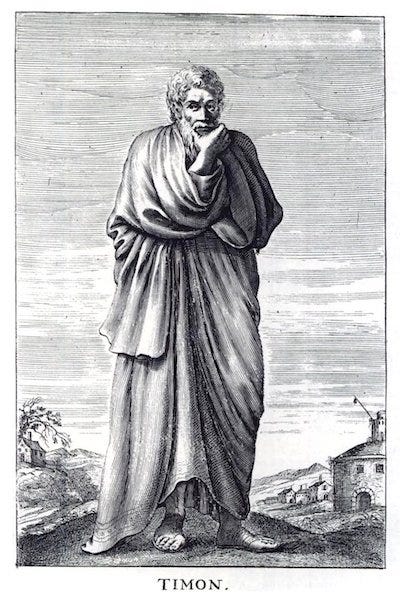

One among many ways to carry out such examination is to consider and answer three questions attributed to Timon of Phlius, who lived between 325-320 and 235-230 BCE (and who is not to be confused with Timon of Athens, the historical figure that inspired the homonymous play by Shakespeare).

Timon was a student of Pyrrho of Elis, the founder of one of the two branches of ancient skepticism, aptly known as Pyrrhonism. The other branch was Academic Skepticism, which was adopted, among others, by Carneades and Cicero.

Pyrrho didn’t write anything. On purpose. The same annoying attitude shared by Socrates, Carneades, and Epictetus, among others. Timon, by contrast, wrote poems, tragedies, comedies, satiric pieces, and a number of other things. Most of these writings unfortunately survive only in fragments quoted by other authors. The uncertainty is so great that perhaps Pyrrhonism should actually be called Timonism, since some scholars think Timon, and not Pyrrho, was the originator of the philosophy.

Be that as it may, the fourth century Christian polemicist Eusebius of Caesarea mentions the second century Peripatetic Aristocles as reporting three crucial questions posed by Timon. Yeah, I know, not exactly first-hand sourcing, but that’s what we’ve got. Here are the three questions:

“To be happy [we] must consider these three questions: First, how are things by nature? Secondly, what attitude should we adopt towards them? Thirdly, what will be the outcome for those who have this attitude?” (Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica, 14.18.1- 5)

Why don’t we turn this into an exercise in practical philosophizing? Below I will write the Pyrrhonian answers (which Timon, or rather, Aristocles, or to be more precise Eusebius, attribute to Pyrrho himself). Then I’m going to try to articulate my own thoughts about the three questions. But perhaps you could pause here, take some time to write down your own answers, and then come back. Or you can keep reading and do the exercise later. It would be wonderful if you could share your take in the discussion thread.

So, what’s the Pyrrhonian skeptic take on Timon’s questions?

“Pyrrho declared that (i) things are equally indifferent, unmeasurable and inarbitrable. For this reason (ii) neither our sensations nor our opinions tell us truths or falsehoods. Therefore, for this reason we should not put our trust in them one bit, but we should be unopinionated, uncommitted and unwavering, saying concerning each individual thing that it no more is than is not, or it both is and is not, or it neither is nor is not. (iii) The outcome for those who actually adopt this attitude, says Timon, will be first speechlessness, and then freedom from disturbance.” (Eusebius, ibid.)

We can clearly discern here the Pyrrhonist path for a good life:

Since the nature of things is not known to us > it follows that we should suspend judgment about all sorts of matters > from which suspension we will gain freedom from emotional disturbance, known as ataraxia.

My take is somewhat different.

(i) How are things by nature?

I am a scientist living in the 21st century. It makes sense, therefore, for me to accept whatever the most current scientific worldview is as provisionally true, or at least as the best approximation to the truth that we have available.

Obviously, this does not mean that I think scientists are always right, or that science has all the answers. But I treat modern science in the same way as I treat modern medicine and engineering: if I am sick, I go to the doctor; if I want a bridge built, I ask an engineer; if I am curious about how the world works ask a scientist.

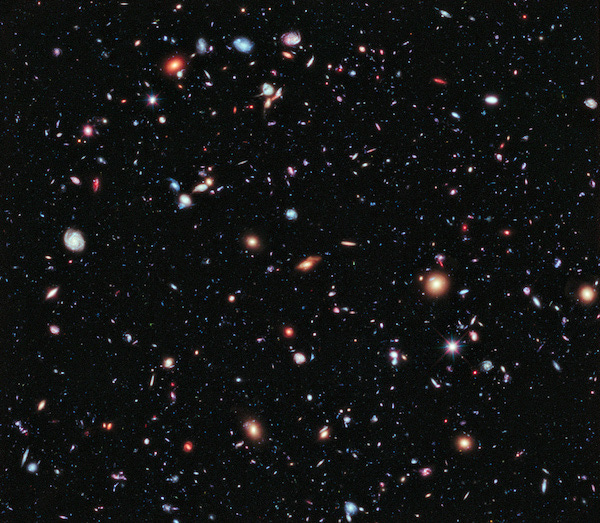

And what does such scientific view of the world look like, at present? Broadly speaking, the universe is made of matter (or quarks, or energy fields, depending on how deep down you go) and—at the macroscopic (i.e., non-quantum) level is regulated by cause-effect. We can discern a number of regularities that we call laws of nature, though we have no clue as to their ultimate origin.

Closer to us as biological beings, we and all other species on Earth are the result of evolution by natural selection and other means. There is nothing special about us, except that we belong to a pretty small branch of the primate evolutionary tree and for likely adaptive reasons developed sociality, intelligence, and language. We have no idea whether there is intelligent life, or any life at all, in the rest of the universe.

Importantly, changes we have caused in our planet’s atmosphere as a result of our technology have started to affect the quality of life of everyone, not to mention threaten the very existence of a large number of other species.

I could go on, but you get the picture. A picture that, again, ought always to be considered revisable, occasionally in a dramatic fashion, though more likely just by small incremental steps.

(ii) What attitude should we adopt towards things?

Our scientific view of the world doesn’t of course dictate any particular attitude toward our own existence, but it does have implications for any life framework one might wish to adopt.

The attitude most in line with my take on (i) above is that we are finite creatures with a certain average life span. We are fundamentally social animals and our chief evolutionary weapon is encased in our skull. It makes sense, then, to use our brain, rather than brute force, to try to solve our problems. It also makes a lot of sense to work on our problems together with other human beings, cooperating at both local and global scales with our evolutionary brothers and sisters.

Given the damage we have already done to our planet, we ought to do whatever is needed to slow it down and, if possible, reverse it. I am convinced that this will include both a technology-based response and a change of attitude that will have us no longer pursue boundless exploitation of natural resources as if there was no tomorrow.

(iii) What will be the outcome for those who have the recommended attitude?

Someone who accepts and internalizes the sort of attitude described in (ii) will be more likely to achieve an internal peace resulting from the fact that they are willing to face the world for what it is, with no indulging in wishful thinking. They will know that they can do their part to help the human cosmopolis, but also realize that there are severe limits to their ability to influence events at large scale.

That kind of person will care for their loved ones as well as for humanity at large, but will understand that whatever the fate of humanity—in either the short or long term—the universe will hardly notice. And that’s okay.

Your turn, dear reader. What are your reflections on Timon’s questions?

As someone with a scientific bent who considers Philosophical Taoism as best expressing my underlying attitude to reality, I would summarize my viewpoint as follows:

1. The Tao is not fully capable of being completely understood in human terms ("The Tao that is written is not the Tao") which is a form of epistemological mysticism.

2. We create theories to explain reality because that is our nature. It is how we function in the world. We tend to see things as binary true/false dualities, for example. There is nothing wrong with that. For the most part it works, as long as we don't get overly attached to our theories. In any case where theory and reality differ, reality always trumps theory.

3. When effecting change in the world, be observant of what gives the biggest bang for the buck. Put another way, if crossing a river, don't fight the current. Or as Reinhold Neibuhr once said "God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can change; and wisdom to know the difference." Speaking as a Pantheist, where the Universe (Tao) is my God, I find that Neibuhr's injunction to be the best course of action.

When I observe, nature is set in a way as to promote renewal and innovation through consumption of already established organics.

The idea for proper attitude in this, nothing is permanent for our senses besides the reality of death, for which we innovate to avoid or mitigate the realization.

Perhaps the end for having this attitude - use and exploration of fuller and experience of nature - is being more part of the experience as a renewal and creator rather then a consumer, and so to be more complete as nature intended.