The story of the pale Stoic in the storm

Stoicism and fear, from the lost Fifth Book of Epictetus

Fear is a basic human emotion. Or is it? It depends on what you mean by “fear.” Modern cognitive science recognizes two different forms of most basic emotions: a pre-cognitive and a cognitive one. In the case of fear, for instance, the pre-cognitive form consists in the feeling you get when an autonomic physiological response is initiated by situations your brain subconsciously recognizes as potentially dangerous. It’s that rush of adrenaline that poises you to act on the fight-or-flight response triggered by your sympathetic nervous system. We share such response with a lot of other animals, and it likely evolved by natural selection.

The cognitive version of fear either follows the fight-or-flight response, once you have had time to think things over, or is an independent, long-term psychological condition. An example of the first kind might be a fight-or-flight condition triggered, say, by suddenly seeing a snake in front of you. After a moment or two the cognitive component starts weaving stories in your conscious brain: “Oh my god, this thing is likely poisonous. It’s going to kill me!” But you have the option of articulating a different story: “Ah, I have read about snakes in this area, and they are usually not poisonous. Besides, the ranger at the entrance of the park has given me instructions on what to do in exactly this situation.” The first story is going to turn your autonomic fight-or-flight response into cognitive fear; the second story will counter it and allow you to deal rationally with the situation.

Long-term psychological fears also have a cognitive component, but they do not originate from a fight-or-flight situation. They result from persistent narratives you tell yourself as a result of other people’s influences, what you read, what you watch on television, and what you see on social media. For instance, you may be afraid of a terrorist attack, even though in most places in the world the chances of this actually occurring are minuscule.

The Stoics drew a distinction between pre-cognitive and cognitive emotions, for instance Seneca, in On Anger, refers to pre-cognitive emotions as “the first movement” that may, or may not—depending on how we act—lead to the full fledged version. He counts blushing as another example of pre-cognitive emotion. Epictetus calls our first reaction an “impression,” to which—if we take our time—we may or may not give “assent,” thus allowing the pre-emotion to proceed to cognitive emotion.

Yet another way of thinking about this is in terms of Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, who in his best-selling Thinking, Fast and Slow, talks about two gears for our brain: System I, which is subconscious, fast, but approximate; and System II, conscious, reliable, but slow. Although there are situations that unfold so quickly that our only choice is to rely on System I, Epictetus’s advice is to, whenever possible, pause and allow System II to come on, so that we can properly question our first impression and see whether we do wish to act on it or not.

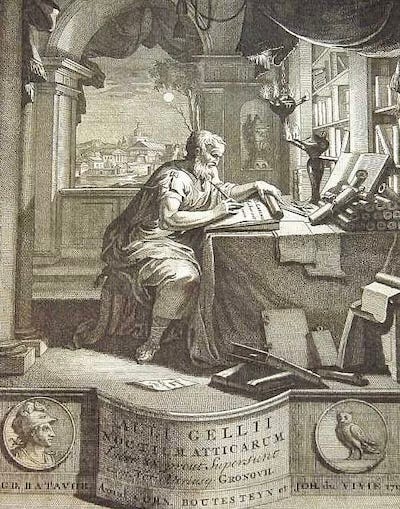

I’m telling you all of this because the other day, in the middle of an online discussion for a course I’m teaching on Seneca’s Letters, one of my students brought up a classic instance of the difference between impressions and assent in the Stoic literature, a story told by Aulus Gellius (125-180) in his Attic Nights (specifically, at 19.1). I’m going to transcribe the full (fairly long, sorry!) passage and intersperse a bit of commentary, as needed. It begins thus:

“We were sailing from Cassiopa to Brundisium over the Ionian sea, violent, vast and storm-tossed. During almost the whole of the night which followed our first day a fierce side-wind blew, which had filled our ship with water. Then afterwards, while we were all still lamenting, and working hard at the pumps, day at last dawned. But there was no less danger and no slackening of the violence of the wind; on the contrary, more frequent whirlwinds, a black sky, masses of fog, and a kind of fearful cloud-forms, which they called typhones, or ‘typhoons,’ seemed to hang over and threaten us, ready to overwhelm the ship.”

Cassiopa was a town in the north-eastern part of Corcyra, modern Corfu, near the northwestern border of Greece. Aulus is setting the dramatic scene here, letting us feel the senario: a powerful storm is battering the ship at night, and it does not abate the following day.

Notice the use of the word “typhoon” to describe the storm. Typhon was a gigantic monster in the form of a serpent, and one of the most deadly creatures in all of Greek mythology. According to Hesiod, he was the son of Gaia (the personification of Mother Earth) and Tartarus (the deep abyss where the Titans and wicked souls are imprisoned and tortured). Aulus continues:

“In our company was an eminent philosopher of the Stoic sect, whom I had known at Athens as a man of no slight importance, holding the young men who were his pupils under very good control. In the midst of the great dangers of that time and that tumult of sea and sky I looked for him, desiring to know in what state of mind he was and whether he was unterrified and courageous. And then I beheld the man frightened and ghastly pale, not indeed uttering any lamentations, as all the rest were doing, nor any outcries of that kind, but in his loss of color and distracted expression not differing much from the others.”

Aulus turns to look at the unnamed Stoic onboard because he is curious whether the Stoics’ reputation for courage and control of their emotions is true. At least initially, he is disappointed, because the philosopher in question is pale and appears frightened. However, notice that the Stoic is not given to outcries of fear, as many of the others are. This will become significant a bit later.

“But when the sky cleared, the sea grew calm, and the heat of danger cooled, then the Stoic was approached by a rich Greek from Asia, a man of elegant apparel, as we saw, and with an abundance of baggage and many attendants, while he himself showed signs of a luxurious person and disposition. This man, in a bantering tone, said: ‘What does this mean, Sir philosopher, that when we were in danger you were afraid and turned pale, while I neither feared nor changed color?’ And the philosopher, after hesitating for a moment about the propriety of answering him, said: ‘If in such a terrible storm I did show a little fear, you are not worthy to be told the reason for it. But, if you please, the famous Aristippus, the pupil of Socrates, shall answer for me, who on being asked on a similar occasion by a man much like you why he feared, though a philosopher, while his questioner on the contrary had no fear, replied that they had not the same motives, for his questioner need not be very anxious about the life of a worthless coxcomb, but he himself feared for the life of an Aristippus.’”

Ouch! Aristippus was not only a student of Socrates, as Aulus reminds us, but also the founder of the hedonistic sect of the Cyrenaics. Both Aristippus’s and the unnamed Stoic’s response may appear more than a bit rude, but the key here is the description of the respective questioners as “coxcombs,” i.e., conceited dandies, fops. Evidently, it was the custom of the time for philosophers to put such overbearing people in their place. But the story continues:

“With these words then the Stoic rid himself of the rich Asiatic. But later, when we were approaching Brundisium and sea and sky were calm, I asked him what the reason for his fear was, which he had refused to reveal to the man who had improperly addressed him. And he quietly and courteously replied: ‘Since you are desirous of knowing, hear what our forefathers, the founders of the Stoic sect, thought about that brief but inevitable and natural fear, or rather,’ said he, ‘read it, for if you read it, you will be the more ready to believe it and you will remember it better.’ Thereupon before my eyes he drew from his little bag the fifth book of the Discourses of the philosopher Epictetus, which, as arranged by Arrian, undoubtedly agree with the writings of Zeno and Chrysippus.”

Wait, what? The fifth book of Epictetus’s Discourses? But there are only four of them! In fact, Arrian of Nicomedia, the student of Epictetus who wrote both the Discourses and the Enchiridion, compiled eight volumes of the first, of which only four survive. We know of the other four precisely because of fragments reported by a scatter of later author, including Aulus Gellius and Marcus Aurelius.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Figs in Winter: a Community of Reason to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.