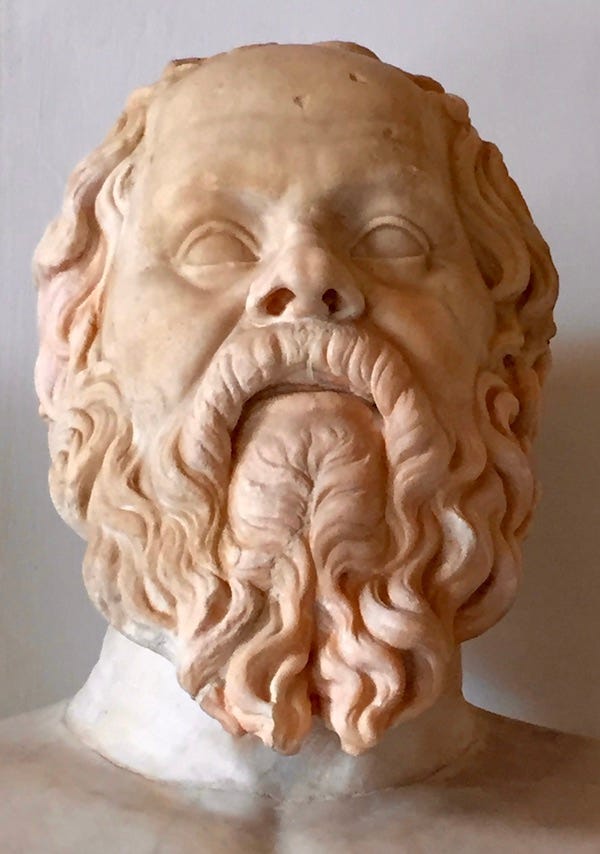

How is it possible that human beings commit atrocities like the Holocaust or the Rwandan genocide? Or torture people like the Spanish Inquisition did, and ISIS and similar groups still do today? That’s a question that has been debated in philosophy at least since the time of Socrates, who had some very insightful things to say about it, as we shall see. Nowadays, the study of evil is shaping up as a multidisciplinary inquiry, where natural science, social science, and philosophy interact constructively.

In this context, I’d like to highlight certain concepts from a fascinating article that appeared in the excellent Aeon magazine: “How evil happens,” by Noga Arikha. Arikha covers a lot of territory, and I highly recommend reading her essay in full, but here I wish to focus on an aspect that is both important and yet difficult for many to accept: “evil” is often done by perfectly normal people, who are moreover convinced that they are doing the right thing.

Consider for a moment Heinrich Himmler’s speech in Poznan in 1943. Among other things he said: “We have the moral right, we had the duty to our people to do it, to kill this people who wanted to kill us.” Sure, you may dismiss Himmler himself as a psychopath (though was he, really?). But you can’t likewise dismiss the millions of Germans who acted accordingly, either in direct support of the Nazi regime or by way of complacency. They were not all psychopaths, nor is it tenable that they were all acting under the threat of a gun to their head. (If you are not convinced, read this review of two books exploring ordinary lives under Nazism.)

Arikha’s interest focuses on research concerning the neural correlates of “evil” behavior, and highlights how it is pharmacologically inducible: “the amphetamine Captagon—used, inter alia, by ISIS members—affects dopamine function, depletes serotonin in the orbitofrontal cortex, and leads to rigid, psychopathic-like behavior.”

Luckily, though, she doesn’t fall for a simplistic “your brain on X” kind of approach. She recognizes that just because we can induce a given behavior artificially, and because we find neural correlates of that behavior, it doesn’t mean that the neurological level of analysis is the only one that matters, or even necessarily the most important one. She elaborates:

“Much as the neurosciences are an exciting new tool for human self-understanding, they will not explain away our brutishness. Causal accounts of the destruction that humans inflict on each other are best provided by political history—not science, nor metaphysics.”

That’s exactly right, and a point often under-appreciated in this era of scientism and hyper-reductionism (two sins of which, ironically, I’m often accused of, despite my constant struggle to keep a balanced view—but that’s a discussion for another time). We are story telling animals, we use narratives to structure and make sense of our lives, and these narratives can lead us to very positive or unspeakably horrible behaviors—though we always manage to convince ourselves that what we do is justifiable.

One common suggestion is that evil the result of lack of empathy, that ability we think we have to feel what another person feels. We hear right and left that we need to cultivate empathy, that there is a “empathy erosion,” in the words of psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen. But other psychologists, like Paul Bloom, author of Against Empathy, are beginning to push back, and for good reasons. Yes, human beings who are incapable of empathy are guaranteed to be psychopaths, but—again—that bio-neurological disease has not, in fact, struck millions of people across cultures and history. As Arikha writes:

“Empathy is not always a reliable guide to appropriate behavior—we don’t feel empathy for the insects dying because of climate change, for instance, but we can decide rationally to act against the disaster. It can even lead to bad decisions with regard to those at whom it is directed—a surgeon who feels empathy for the patient under drapes should really not operate.”

It actually goes deeper than that. As the author herself emphasizes, empathy probably evolved to increase group cohesion early on in human prehistory, but is, ultimately, a parochial feeling. Revenge thrives on empathy, and it can easily nurture xenophobia: it comes natural to us to feel compassion for members of the in-group, but it also comes natural to feel hatred (itself based on fear) for members of the out-group.

That is why Bloom in his book talks of the need to develop “rational compassion,” which is not at all the oxymoron that at first it may appear to be. It is otherwise known as sympathy, the ability to reason compassionately, even when we are incapable of actually putting ourselves in the other person’s shoes. I cannot imagine, for instance, what it was like to be a slave in 19th century America, it is simply too far from my personal experience, thankfully. So empathy fails me here. But I can draw on sympathy and very much feel a sense of injustice against the human condition, of oppression of the weak, of something, that is, that needs to be opposed with all one’s might.

Socrates had already gotten there, way before the availability of neuroimages and the set of modern psychology. Consider this passage, from Plato’s Protagoras, where Socrates says:

“For me, I’m pretty sure that, among philosophers, there is not one who thinks that a man sins willfully and voluntarily makes shameful and evil actions, they all know the contrary, that all who actions are shameful and wrong to do so involuntarily.” (352c)

Socrates was probably a bit optimistic about there being a consensus among philosophers on anything, but he otherwise was onto something important. The idea is often summarized as “people do evil because of ignorance,” which strikes most of us as not just bizarre, but pernicious. What, you think Hitler didn’t know what he was doing??

But the Greek word here is amathia, which does not really translate as ignorance, but rather as un-wisdom. People do evil because they don’t know better. Yes, even Hitler, the quintessential example of evil “personified” (talk about bad metaphysics!) actually had (really, really, bad) reasons for what he was doing. He, like Himmler above, was convinced that Jews were a threat to the German people, and moreover that Aryan Germans truly were a superior race. This is all nonsense on stilts, of course, but it isn’t just a convenient and conscious rationalization, people really believe this stuff. And act accordingly.

We all suffer from amathia, to a higher or lesser degree. It’s, in a sense, a spiritual disease, meaning a condition that negatively affects the human spirit, that interferes with our ability to express sympathy, and that takes advantage of, and warps, our ability for empathy. The cure, for Socrates like for the ancient Stoics who were inspired by him, is therefore spiritual training, i.e., philosophy in the original sense of the word: love of wisdom.

In fact, the Stoics were among the first philosophers to openly embrace an idea that universalizes sympathy to the entire human race: cosmopolitanism. We are all human beings, of equal dignity by virtue of being human. Which means no discrimination by gender, nationality, ethnicity or anything else. So why don’t we practice a little cosmopolitanism every day, following Epictetus’s advice:

“Do as Socrates did, never replying to the question of where he was from with, ‘I am Athenian,’ or ‘I am from Corinth,’ but always, ‘I am a citizen of the world.’” (Discourses I, 9.1)

Thank you, as always. I'm not just interested in a post mortem of past evil, but finding an understanding of current evil before it becomes too malignant. I think certain ways of thinking and feeling bring about evil. It doesn't have to be a genocidal evil; evil is rooted in a cult of personality. What made George Washington an example of Good is not his competency as a general or as a president. But the fact he resisted the creation of a cult of personality, refused to seek a third term, and stepped down to return to his farm, like Cincinnatus.

The creation of a cult of personality is a path to evil. Having read years ago about the rise of Fascism in Italy and the rise of Nazism in Germany, I see how Religion and other Ideology can be evil. Without blind faith in a religious or secular teleological myth, evil people will do evil things, and good people will do good things. But with such blind faith, otherwise Good people will cheerfully do evil things: Community building, selfless charity, cheerfully committed to an evil end.

Thus, besides these historical and sociological text I read forty years ago, I was reminded of a recent news article when I read your piece. In it, The New York Young Republican Club issued a statement saying “President Trump embodies the American people — our psyche from id to super-ego — as does no other figure; his soul is totally bonded with our core values and emotions, and he is our total and indisputable champion.”

Lotsa interesting info! Thx. Looking forward to an oxytocin booster shot for men!