Suggested Readings

A few recommendations by Figs in Winter for your reading pleasure

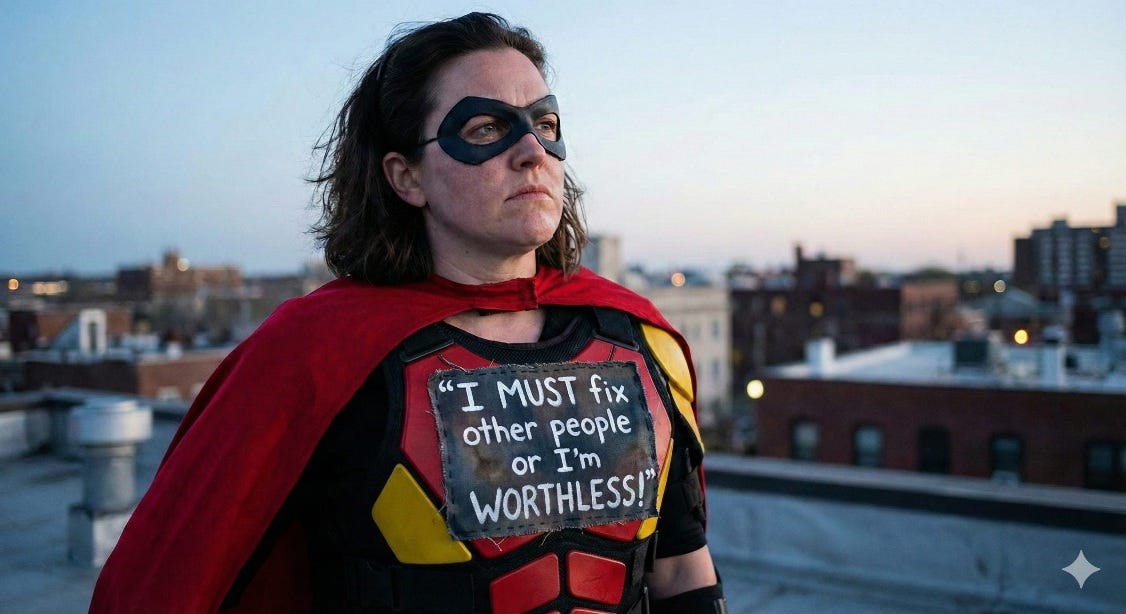

Coping with your emotions. Most of the coaching that I currently do draws on the Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT) of Albert Ellis, as well as elements of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and other modern evidence-based therapies. However, I use a version of Aaron T. Beck’s AWARE acronym, from Cognitive Therapy, to summarize my advice about coping with certain emotions, as I find that can make the steps easier to remember.

A = Accept your Feelings

W = Watch your Thoughts

A = Act in Accord with your Values

R = Repeat Rational Statements

E = Exercise Between Episodes

… (Donald Robertson's Substack)

The obligation to restrict AI in student writing. I have had students attempt to submit essays containing AI-generated text as their own. Call this student practice “AI appropriation.” I do not allow AI appropriation in written assignments. I believe that every teacher and every university has a strong obligation to forbid AI appropriation. This is because AI appropriation is morally parallel to plagiarism. Accordingly, universities and teachers who allow students to use AI in cases where they would forbid dependence on other persons are in a position parallel to allowing plagiarism. … (New Works in Philosophy)

Your red is my red, at least to our brains. It’s a late-night debate in college dorms across the world: Is my red the same as your red? Two neuroscientists weigh in on this classic “Intro to Philosophy” puzzler in research published September 8 in the Journal of Neuroscience. Their answer is a resounding maybe. There were two possibilities when it comes to how brains perceive color, says Andreas Bartels of the University of Tübingen and the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Germany. Perhaps everyone’s brain is unique, with bespoke snowflake patterns of nerve cells responding when a person sees red. Or it could be that seeing red kicks off a standard, predictable pattern of brain activity that doesn’t vary much from person to person. … (Science News)

Weltschmerz and the world. The most famous pessimist in the history of philosophy is surely Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860). In his most important work, The World as Will and Representation (1818) he describes our existence as ‘a mistake’ and ‘the worst of all possible worlds’, explaining that, except in occasional moments of artistic delight, humans are trapped in an endless painful cycle of desire, frustration, and boredom. For Schopenhauer, “pain, not pleasure, is the positive thing, pleasure being merely its absence” and life, if properly understood, “ought to disgust us”. Alongside suffering and distraction, our overall moral condition is also terrible: other than a few ‘beautiful souls’, people are dominated by “vices, failings… of all sorts”, and the social world is a “den of thieves”. Suicide is morally ruled out, so our only path to redemption is to try, however futilely, to transcend the will that relentlessly drives all things. True to his pessimism, though, this transcendence is confined by Schopenhauer to an elite group – to ‘saints and geniuses’ – condemning the rest of us to the hell of human existence. While Schopenhauer is the most famous pessimist, he was not the only pessimist in nineteenth century Germany, nor was he considered the most important at the time. Excellent recent studies of the history of pessimism – such as Frederick Beiser’s Weltschmerz (‘ World-pain’, 2016) – challenge the Schopenhauer-centred picture, reminding us of other, now-forgotten figures. … (Philosophy Now)

What is Aristotelian prohairesis? What exactly is the moral phenomenon Aristotle picks out in his works by “prohairesis”? Interpreters of Aristotle head in several diverging directions. For some, prohairesis remains an unproblematic concept, whose entire nature and scope we understand well enough from its Nicomachean Ethics bk. 3.2. characterization as “deliberate choice”. For others, Aristotle’s conception of prohairesis is not quite so simple, clear, or straightforward. Without simply rejecting the N.E .3.2 discussion, such interpreters sense that those passages cannot comprise the entirety of the story. Some suspect that a deep incoherence or lacuna underlies Aristotle’s numerous discussions and uses of prohairesis. Others attempt to rework an Aristotelian notion of prohairesis into something more amenable to (because more alike to) conceptions germane to later moral theories. Others more optimistically attempt to provide more or less integrated and systematic interpretations ranging across Aristotle’s corpus. … (That Philosophy Guy)