Stoicism, emotions, and the “irrational tug”

The Stoics evolved a remarkably modern and effective view of emotions

One of the most persisting stereotypes about the Stoics is that we go around sporting a stiff upper lip, constantly trying to suppress our emotions. Kind of a bunch of Mr. Spock from Star Trek. With all due respect to Spock, one of my favorite characters from that or any franchise, nope, that ain’t it.

The Stoics divided emotions into two broad categories: healthy ones, known as eupatheiai (singular, eupatheia) and unhealthy ones, referred to as pathē (singular, pathos, the root of the modern English word “pathology”). The unhealthy emotions are also referred to as “passions,” not as in “I have a passion for classical music,” but rather as in “I’m getting really angry and I’m going to punch someone.”

[Before we proceed any further: by far the best, and arguably definitive treatment of Stoic emotions is found in a highly recommended book by Margaret Graver. You’ll find a short authorized summary here.]

What determines the healthy or unhealthy status of an emotion is whether, it is aligned with reason or tends to counter and overwhelm it. For instance, love for one’s partner, children, and friends, or—more broadly—love for humanity (philanthropia) are all eupatheiai, because reason approves of such emotions. This approval is the result of the fact that we are social animals, so that to “live in accordance with nature,” as the famous Stoic motto goes, means to love all human beings. It follows that we ought to mindfully cultivate the healthy emotions.

Unhealthy emotions, the so-called passions, by contrast, lead us to behave unvirtuously, which from the Stoic perspective means irrationally. Anger, for instance, tends to be destructive and anti-social, which is why we should try at all costs to stay away from it.

But hold on a second, you may reasonably say, emotions are emotions, I don’t have any rational control over them, which means that it really isn’t up to me to cultivate the healthy ones and eliminate the unhealthy ones, is it?

Wrong. According to Stoic theory—as well as to modern cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—the emotions are at least partially cognitive, meaning that they result from whatever story we tell ourselves in reaction to what is happening. If someone insults you, for instance, you might (mostly unconsciously) tell yourself that being insulted is really, really bad, and that you ought, just ought to do something about it. Something drastic, in fact, like yelling at or even punching the bastard.

But if this is true, then you actually have the power, with patience and training, to better regulate your inner dialogue, to reshape and reframe the stories you tell yourself, like: “Insult? What is that? Just air coming out of someone’s mouth, effective only if I let it. And I won’t let it. Instead, I’ll just walk away.”

We know this works because there is tons of empirical evidence that CBT works, and CBT originated in the 1960s from insights that people like Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck gathered directly from Stoic theory and practice.

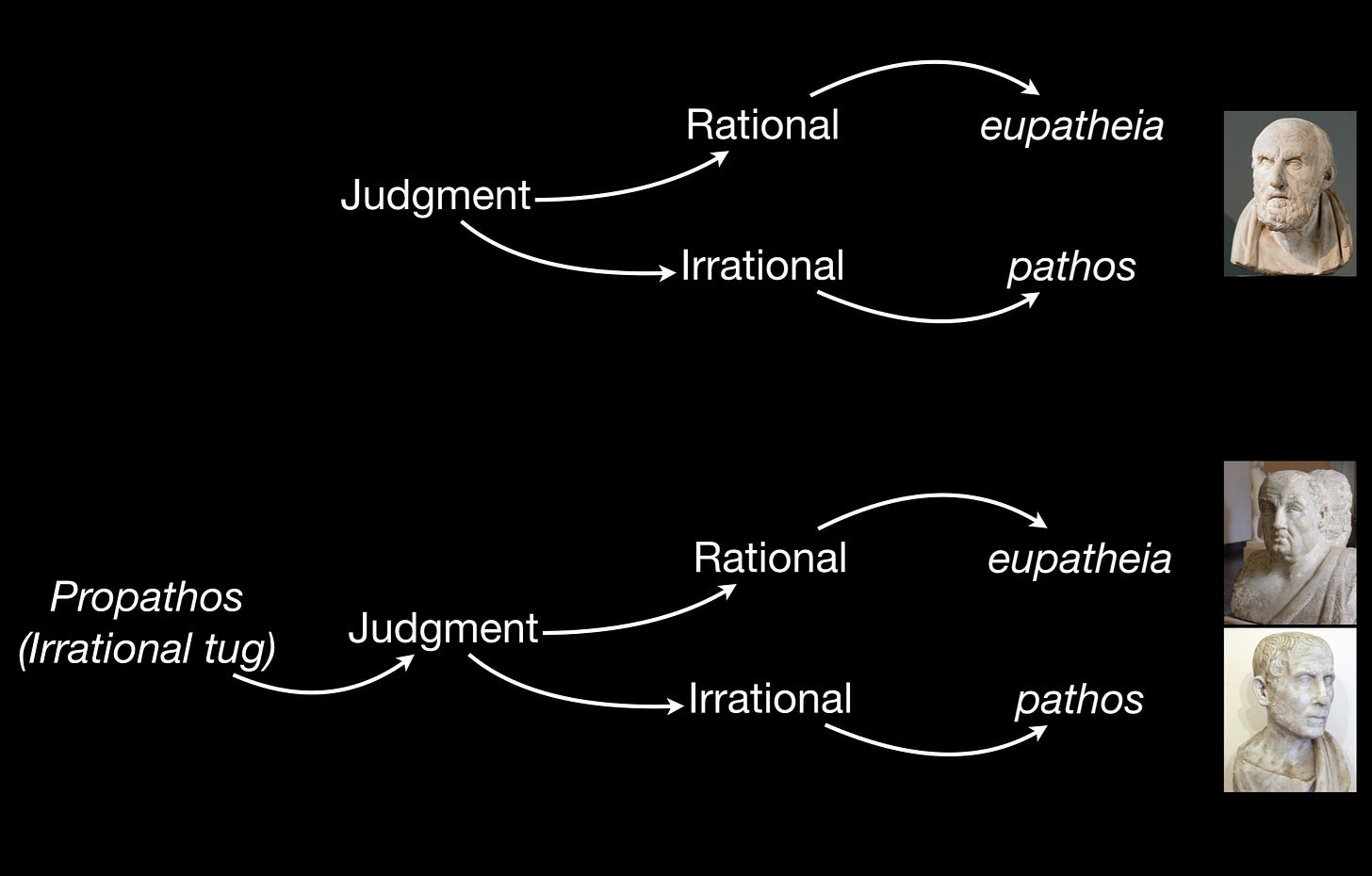

So far, the standard story. But it’s a bit more complicated, and fascinating, than that. There are actually at least two (possibly three) Stoic accounts of emotions, due to Chrysippus of Soli (the third scholarch of the original Stoa, 279-206 BCE), Posidonius of Apamea (135-51 BCE), and Seneca the Younger (4 BCE-65 CE). Let’s take a look.

The standard model: Chrysippus

The earliest and most enduring Stoic model of emotions is attributed to Chrysippus. Perhaps in agreement with the fact that he was a logician, the model is entirely rationalistic: all emotions are cognitive in nature, so that the when we act (and feel!) irrationally this is because of a defect in reasoning. The good news, of course, is that we can correct such defect, which is something that most of us will struggle with and yet will still manage at least occasionally. The sage, the ideal Stoic, will of course be able to do that all the times. This model looks like the top diagram in the figure below.

Notice that Chrysippus’s theory was in stark contrast with the Platonic account, as laid out, for instance, in the Republic. There Plato tells us that the soul has three independent components: a rational one, a “spirited” one, and an “appetitive” one. The rational aspect ought to be in charge, but the task is difficult, as exemplified in the famous metaphor of the chariot: the charioteer is the rational soul, whereas the two wild horses are the spirited and appetitive souls.

Chrysippus’s model has the benefit of providing us with the framework to practice both Stoicism and cognitive behavioral therapy. However, it also seems a bit too easy and does not really correspond very well with our experienced reality. Not only it isn’t easy to reason with our emotions, the model simply leaves unexplained a number of common phenomena, as pointed out in a series of objection by a later Stoic, Posidonius. For instance, how come we are emotionally affected by instrumental music, which clearly has no cognitive content at all? Also, why do very young children and animals display emotions, even though their cognitive abilities—in the sense of conscious, deliberate articulation of their thoughts—are either embryonic or non-existent? And why do some emotional reactions persist even after we’ve carried out a good rational analysis? (For instance, we are still angry, or sad, even though we agree with ourselves that we shouldn’t be!) Clearly, something more is needed.

The three movements: Seneca

On Anger, by Seneca, is the best and most comprehensive Stoic treatment of emotions that has survived to modern times. And it still provides excellent advice, rivaling what you find on the anger management site of the American Philosophical Association. In that book, Seneca presents a famous “three movements” model of anger, where he says:

“That you may know in what manner passions begin and swell and gain spirit, learn that the first movement is involuntary, and is, as it were, a preparation for a passion, and a threatening of one. The next is combined with a wish, though not an obstinate one, as, for example, ‘It is my duty to avenge myself, because I have been injured,’ or ‘It is right that this man should be punished, because he has committed a crime.’ The third movement is already beyond our control, because it overrides reason, and wishes to avenge itself, not if it be its duty, but whether or no.” (II.4)

So, according to Seneca, the typical sequence leading to a passion is: pre-emotion > cognitive assessment > overriding of reason. The second and third phases are already embedded in Chrysippus’s account, but the first one appears new, though Graver says it was not, in fact, Seneca’s invention. He apparently made vivid and explicit what previous Stoics had already put forth.

Be that as it may, the so-called “pre-emotions,” in Greek propatheiai, make the Stoic model more sophisticated and closer to modern understanding (second diagram in the figure above). An example will help clarify the distinction between what Seneca is saying and the standard Chrysippean model. Consider, again, anger. The term means different things even to different contemporary scientists, depending on their discipline. If you look at it from the point of view of neurobiological mechanisms, “anger” is the physiological response induced by the sudden release of adrenalin by the amygdala. You can literally feel the surge in your body, commonly referred to as the “fight-or-flight” response. But for a psychologist “anger” has a cognitive component: you feel the physiological change and you account for it in terms of your internal monologue. “I’m angry because…” Chrysippus’s theory focuses on the cognitive aspect, which surfaces during Seneca’s second movement. But Seneca is right that this is preceded by an entirely involuntary prelude, the propathos, or first movement.

The pre-emotions are important, then, because they better explain the available empirical evidence and also begin to answer Posidonius’s objections discussed earlier. We are affected by instrumental music not at the cognitive, but at the pre-emotional level; animals and very young children do not experience cognitive emotions, but they do experience Seneca’s first movement; and so on.

The irrational tug: Posidonius

Posidonius occasionally used a different term that doesn’t appear in the early Stoic literature to refer to affective phenomena that take place before cognition kicks in: pathētikē kinēsis, literally “movement of the passions,” sometimes translated by modern scholars as “irrational tug.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Figs in Winter: a Community of Reason to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.