Stoicism and emotions: a guide for modern practitioners

We talk a lot about “unhealthy” emotions, but how do we cultivate the healthy ones?

For the past couple of years I’ve been a member of an informal Stoic practice circle organized by my friend and co-author Greg Lopez. Recently we had a conversation about Stoicism and emotions, whereby I brought up one of my own difficulties with the path of the Stoa: as much as I try to think of people—especially public figures like politicians—as not doing evil on purpose, instead acting as they do out of lack of wisdom, I have a hard time not passing judgment on them whenever their actions negatively affect countless people.

To better understand the problem let’s go over the basic Socratic-Stoic concept that people err because of “unwisdom,” “disknowledge,” or “intelligent stupidity” (amathia in Greek). Here is how Epictetus explains the concept to one of his students:

“‘They are thieves,’ says someone, ‘and robbers.’ — What do you mean by ‘thieves and robbers?’ They have simply gone astray in questions of good and evil. Ought we, therefore, to be angry with them, or rather pity them? Only show them their error and you will see how quickly they will desist from their mistakes. But if their eyes are not opened, they have nothing superior to their mere opinion. ‘Ought not this brigand, then, and this adulterer to be put to death?,’ you ask. Not at all, but you should ask rather, ‘Ought not this man to be put to death who is in a state of error and delusion about the greatest matters, and is in a state of blindness, not, indeed, in the vision which distinguishes between white and black, but in the judgement which distinguishes between the good and the evil?’ And if you put it this way, you will realize how inhuman a sentiment it is that you are uttering, and that it is just as if you should say, ‘Ought not this blind man, then, or this deaf man to be put to death?’ For if the loss of the greatest things is the greatest harm that can befall a man, while the greatest thing in each man is a right moral purpose, and if a man is deprived of this very thing, what ground is left for you to be angry at him? Why, man, if you must be affected in a way that is contrary to nature at the misfortunes of another, pity him rather, but do not hate him: drop this readiness to take offence and this spirit of hatred.” (Discourses 1.18)

I transcribed the full passage because it is one of the most beautiful and profound things Epictetus says. He is arguing that people who do bad things act out of a particular type of ignorance, not of facts, but of the distinction between good and evil. They are affected by a special type of blindness, which undermines their own character, and is therefore a kind of self-harm. Epictetus counsels us to pity such people, not to be angry with them.

At an intellectual level, I do think that’s the best explanation for human behavior. And I endorse it at an ethical level because it makes all of us more compassionate and less judgmental. But I’m having difficulties aligning my emotions with my understanding. When I see a politician doing something that will potentially hurt thousands or even millions of people I think to myself: “He is suffering from amathia, so he needs to be pitied, though that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t oppose his policies in any way I can.” But what I feel is more akin to “that f*ing bastard, how can he possibly get away with this??” This misalignment between my reason and my emotional responses is either a sign that my reason got it wrong or that I have not worked hard enough to align my emotions with my assessment of the situation. Since I do buy into the Stoic framework, the problem appears to be emotional, not logical.

To expand a bit about why exactly I agree with Epictetus, consider that—like him—I don’t believe in free will. I think of people has sophisticated biological decision making systems. When we make a decision—good or bad—it is the result of a complex web of cause-effect that led to that decision, a web that includes our genetic makeup, the environment in which we grew up, the experiences we have had since, and the way we processed such experiences. If someone’s decision is bad, their internal assessment system has gone awry, and the only reasonable responses we have available are to (a) attempt to minimize any potential negative consequence to others and (b) see if we can help the individual in question to correct their faulty internal processing (i.e., to educate him).

Okay, so given the above, why is my rational deliberation about this matter misaligned with my emotional response? Mind you, mine is not an unusual predicament, and I would be like a sage if I didn’t experience the problem. Nevertheless, when I brought up the issue in the practice circle we had an interesting discussion about how to make progress. And that discussion focused mostly on the Stoic conception of emotions. I came out of the exchange with my fellow practitioners with an urge to go back and see if I could modernize the Stoic take in a manner that might be more useful to modern students of the Stoa. Here is what I came up with.

The plan of this essay is to briefly examine why modern Stoic conceptions of emotions are, in my opinion, somewhat lacking; to take a brief survey of what contemporary science has to say about the issue; and then to propose a framework that I’m hoping will be useful also to other people.

Modernizing Stoic emotions: what’s missing?

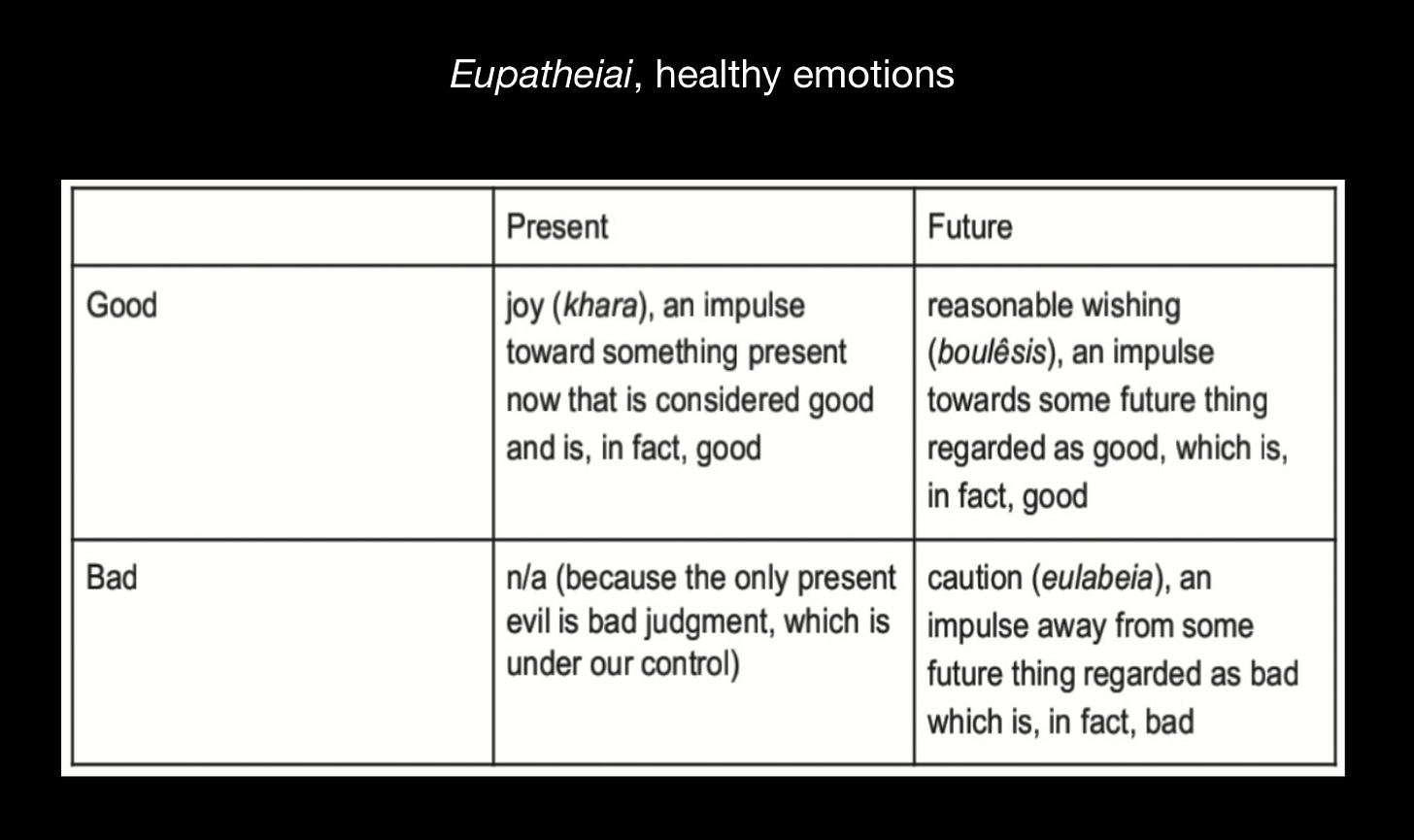

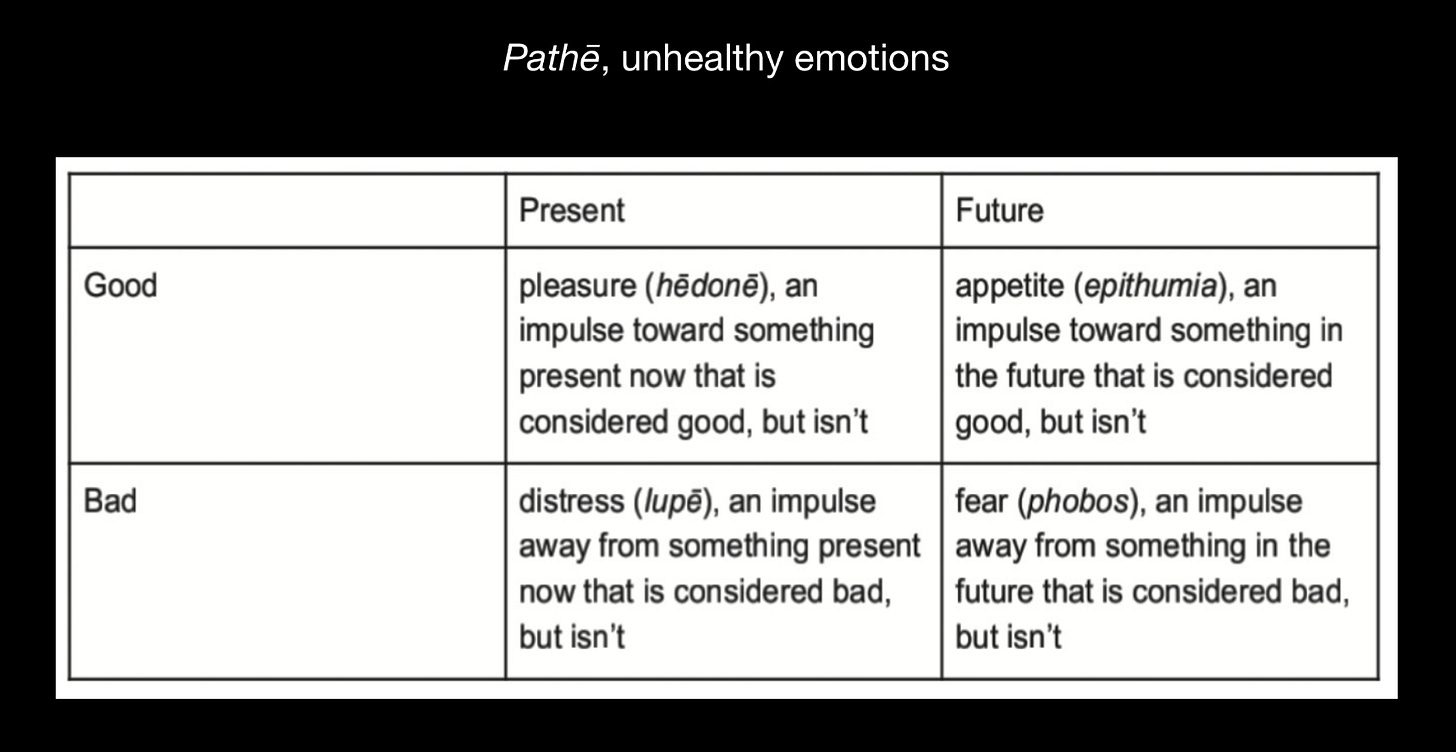

Ancient Stoics distinguished between unhealthy emotions (pathe) and healthy ones (eupatheiai), arguing that while we all experience the first, only the sage is capable of true eupatheiai. One issue with this, other than the obvious scarcity of sages, is that I think modern audiences need a more intuitive, practical approach. Based on my understanding of the pertinent literature in contemporary academic philosophy, psychology, and therapeutic frameworks, below I’m going to introduce a dial metaphor to help modernize how we understand and cultivate emotionally wise responses while maintaining philosophical integrity. As we shall see, the model rejects the classic Stoic strict dichotomy between healthy and unhealthy emotional responses, more realistically conceptualizing human emotions along a continuum from unhelpful to helpful (to human flourishing).

The framework I’m about to propose addresses what I believe to be a gap in the ancient treatment of emotions: while Margaret Graver’s scholarly work provides the definitive academic treatment of Stoic emotions, it remains too technical for general audiences. Her book, “Stoicism and Emotion,” provides the gold standard of scholarship but is “pitched to readers well versed in ancient Greek literature with a fair degree of philosophical training,” as noted by the Bryn Mawr Classical Review. The work focuses heavily on philological analysis of ancient texts rather than practical application, leaving general audiences without actionable frameworks.

Classical Stoicism’s original system of four destructive passions (distress, fear, appetite, pleasure) and three healthy emotions (joy, wish, caution) provides us with an interesting philosophical foundation but lacks the nuanced guidance needed for modern emotional challenges. Its asymmetrical structure—with no healthy counterpart to distress—reflects the ancient focus on sage-level perfection rather than practical progress for everyday practitioners.

Contemporary Stoic practitioners like William Irvine and especially Donald Robertson have made the philosophy more accessible but they too tend to focus on unhealthy emotions like anger and anxiety, and we still have not developed a comprehensive modern Stoic account of healthy emotions. So far as I know, no existing Stoic modernization effort (even the best one, by Larry Becker) uses spectrum or dial metaphors, despite these being natural fits for making emotion regulation more intuitive.

What does the science say?

Modern neuroscience provides overwhelming validation for the Stoic approach of cultivating different emotional responses rather than suppressing feelings. Research by James Gross and colleagues consistently demonstrates that suppression—trying not to show emotions—only targets behavioral expression while leaving subjective experience and physiological activation unchanged. Worse, suppression actually increases stress hormones, impairs memory, and damages relationships.

In contrast, cognitive reappraisal—changing how we interpret situations before emotions fully develop—modifies the entire emotional response. People who use reappraisal show better psychological wellbeing, stronger social connections, and superior physical health outcomes. This directly validates the Stoic emphasis on examining our judgments about circumstances.

Lisa Feldman Barrett’s research on emotional granularity provides additional support. People who can distinguish finely between emotional states—separating “sad” from “disappointed” from “dejected”—have 30% more flexibility in emotion regulation and significantly better health outcomes. This confirms the Stoic practice of precise emotional awareness as foundational to wisdom.

Perhaps most importantly, modern neuroscience reveals that emotion and cognition aren’t separate systems in conflict but work through sophisticated integration. The prefrontal cortex coordinates with rather than simply overrides limbic structures, supporting the Stoic view that wisdom emerges from proper relationship between reason and feeling.

In practical terms, both Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Dialectical Behavior Therapy provide tested models for distinguishing skillful from unskillful emotional responses (as Buddhists would put it). These frameworks offer language and methods that could enhance Stoic modernization efforts.

CBT’s emphasis on “helpful vs. unhelpful” patterns rather than “healthy vs. unhealthy” emotions creates space for context-dependent evaluation, recognizing that the same emotion might be constructive or destructive depending on intensity, duration, and circumstances.

DBT’s “Wise Mind” concept provides a particularly relevant model: integrating “emotion mind” (feelings drive decisions) and “reasonable mind” (logic) into balanced awareness where reason and emotions overlap. This framework offers practical tools for the kind of integration Stoics seek while avoiding the false dichotomy between thinking and feeling.

A reason-aligned emotion dial

Building on these insights, perhaps a reason-aligned emotion dial metaphor may provide us with an intuitive framework for understanding and cultivating wise emotional responses. Rather than categorical distinctions between “good” and “bad” emotions, the dial represents emotional responses along a spectrum from reason-undermining to reason-aligned, with practical gradations for daily use. The dial has three zones:

Red Zone: reason-undermining responses. These are intense reactions that cloud judgment and lead to decisions we later regret. For example:

Explosive anger (destroys relationships, impairs problem-solving)

Paralyzing anxiety (prevents necessary action)

Consuming grief (blocks adaptation and growth)

Addictive cravings (override long-term wellbeing)

Bitter hatred (corrupts character and judgment)

Yellow Zone: emotionally mixed responses. These contain both helpful and unhelpful elements, requiring careful evaluation, like:

Frustrated concern (signals problems but may lead to rumination)

Nervous anticipation (motivates preparation but can become overwhelming)

Righteous indignation (highlights injustice but risks self-righteousness)

Protective worry (shows care but may become controlling)

Green Zone: reason-aligned responses. These emotional responses inform wise action while maintaining clear judgment, as in these cases:

Constructive assertiveness (addresses problems while preserving relationships)

Prudent caution (assesses risks without paralyzing fear)

Adaptive processing (honors loss while enabling forward movement)

Appreciative contentment (finds satisfaction without attachment)

Compassionate strength (combines care with effective action)

The dial metaphor makes emotional regulation intuitive by using language rooted in familiar technology. In the same way in which we adjust volume, brightness, or temperature settings, we can learn to “turn down” destructive intensity while “turning up” wisdom-aligned responses. There are countless applications in major areas of life experience:

For workplace challenges: Instead of explosive anger at inefficient processes, dial toward constructive assertiveness that proposes solutions. Transform nervous anxiety about presentations into purposeful preparation energy that enhances performance.

For relationship conflicts: Rather than bitter resentment about past hurts, dial toward protective boundary-setting that maintains both self-respect and connection. Replace consuming jealousy with appreciative security that strengthens partnership.

For social concerns: Channel paralyzing outrage about injustice into strategic activism that creates sustainable change. Transform xenophobic fear into curious cultural awareness that builds understanding.

It is also, I think, important to develop a precise emotional vocabulary, which expands our regulatory options. As mentioned earlier, research shows that people with higher emotional granularity—the ability to make fine-grained distinctions between feelings—are capable of dramatically enhanced emotional regulation, leading to better life outcomes.

The framework emphasizes function over category, asking “What is this emotion trying to tell me?” rather than “Is this good or bad?” This creates space for wisdom while honoring the intelligence of emotional responses. Instead of suppressing “negative” emotions, then, we strive to develop their wisdom-aligned counterparts:

Anger → Protective advocacy (channeling energy toward justice)

Fear → Strategic awareness (using concern for wise preparation)

Sadness → Honoring grief (processing loss while maintaining social bonds)

Anxiety → Purposeful activation (transforming worry into focused action)

Envy → Appreciative motivation (learning from others’ success)

Hatred → Compassionate boundaries (protecting values without dehumanizing)

The general idea is to learn to maintain the motivational energy of emotions while directing it toward constructive ends through reason, thus avoiding both suppression and indulgence.

Practical implementation strategies

The proposed framework is meant to be implemented through daily practice rather than theoretical understanding alone. Like ancient Stoics who emphasized askesis (spiritual exercise), modern practitioners need systematic methods for developing emotional wisdom. For instance:

Daily dial check-ins: Before important decisions, pause to identify your current emotional zone. Ask: “Am I in the red zone (reason-undermining), yellow zone (mixed), or green zone (reason-aligned)?” This creates space for intentional response rather than automatic reaction.

Emotional weather awareness: Track patterns in your emotional responses across different contexts by way of journaling. Notice what situations tend to push you toward the red zone and develop specific strategies for maintaining green-zone responses in those circumstances.

Wisdom-aligned reframing: When experiencing intense emotions, practice identifying the underlying concern or value, then explore how to honor that wisdom while avoiding destructive expression. Transform the energy rather than suppress it.

Community support: Share the dial framework with trusted friends or colleagues to create accountability and mutual support for emotional growth. Practice becomes more sustainable within supportive relationships.

So, in the end…

The reason-aligned emotion dial is one practical way to bridge the gap between classical Stoic insights and contemporary psychological research. It maintains philosophical integrity by honoring the Stoic emphasis on practical wisdom while providing accessible tools for daily emotional challenges.

This framework transforms the ancient distinction between pathe and eupatheiai into an intuitive system that anyone can apply in modern life. Rather than requiring deep knowledge of Greek philosophy, practitioners can use familiar “dial” metaphors to develop emotional responses that align with their deepest values and clearest thinking.

The approach avoids the false choice between emotional suppression and uncontrolled expression, instead cultivating a third option: emotionally informed wisdom that integrates feeling and reasoning into effective action. This represents not just a modernization of the Stoic treatment of emotions but hopefully an advancement in practical philosophy for contemporary life.

Good read! I agree that this is likely a better way to look at things—it almost seems more Aristotelian, but I suppose not since there is still a “Green Zone” rather than a Golden Mean.

For thinking of politicians, I find it helpful to reflect on the past. Perhaps it’s basically the View From Above, but I just consider all the incompetent and unethical rulers that ruled Rome and the later European Kings and such and remember that we are no different. Politicians are just as susceptible to awfulness as past rulers and people are just as likely to support them!

Thank you, Massimo. That was a truly fascinating article. I really appreciate your in-depth analysis and the division into three zones. I also really like that quote from Epictetus, although I'm rather sceptical about the part: "Only show them their error, and you will see how quickly they will desist from their mistakes." In my experience, pointing out an "unwise" person's mistake often leads not to reflection or correction but to a more aggressive and defensive response. Instead of acknowledging the mistake, they redirect their frustration toward the person who pointed it out.