Some thoughts on Effective Altruism

Would you save a Picasso or a child from a burning building, and why?

Effective Altruism (EA), both the movement and the concept underlying it, has been around now for about one and a half decade and has generated plenty of both enthusiasm and criticism. So I thought it may be time to write about it, in order primarily to help myself get more clear on what the fuss is all about. I hope the following considerations will also be helpful to my readers and stimulate some thought and discussion.

At its core, EA is about “using evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible, and taking action on that basis.” [1] This is, very clearly, something that it’s hard to object to. I, for one, don’t want to reject evidence and act irrationally when it comes to deciding to which charities to donate and how much, for instance. The problems, if any, begin to take form when we dig a bit deeper.

For instance, in terms of its basic philosophy, EA is a combination of 19th century utilitarianism (though the idea has a much longer history) and the modern notion that privileged people in the developed world should devote resources to help the global poor. Again, I find it difficult to argue the second point, but utilitarianism? No thanks. Utilitarianism is one of the three major frameworks in modern moral philosophy, the other two being Kant-style deontology (i.e., duty based ethics) and Greco-Roman style virtue ethics. Since I embrace Stoicism as a philosophy of life, and Stoicism is a type of virtue ethics, I’m naturally skeptical of utilitarianism.

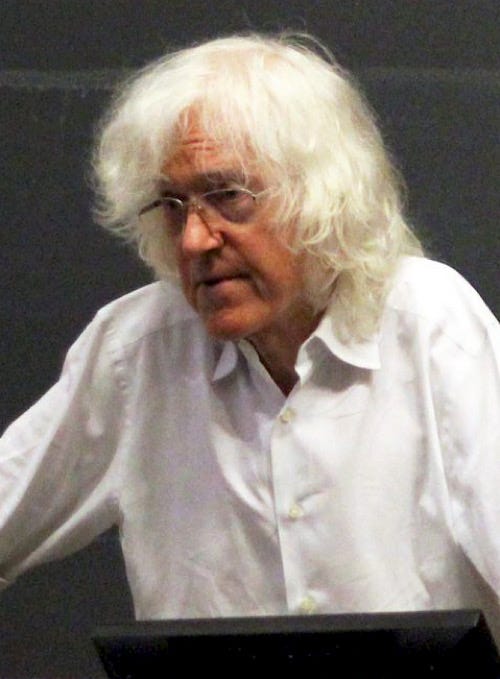

There are a number of issues that can be raised against the 19th century philosophy that began with Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, but one that may make you pause is the so-called repugnant conclusion, a logical consequence of utilitarianism explained by British philosopher Derek Parfit: “For any perfectly equal population with very high positive welfare, there is a population with very low positive welfare which is better, other things being equal” [2]. In other words, consistently applying utilitarianism would result in a world in which everyone would be just above the level of misery [3]. You can see why this conclusion is referred to as “repugnant.”

[Derek Parfit, the philosopher who wrote about the “repugnant conclusion.” Image from Wikipedia, CC license]

Back to EA: historically, it started as a set of techniques to evaluate the effectiveness of a number of charities, but became an official movement with the establishment in 2011 of the Center for Effective Altruism, which has organized the Effective Altruism Global conferences since 2013. The movement currently counts about 7,000 people, mostly from Silicon Valley and a number of elite schools in the US and UK.

From the get go it has been a very odd mix of groups, ideas, and people. In terms of groups, EA includes evidence-based charities like GiveWell, organizations encouraging people to select high-earning careers so that they can give to charities, like 80,000 Hours, and nuts and semi-nuts like The Singularity Institute and the Less Wrong discussion forum.

A look at prominent members reveals another odd mix: philosophers like William MacAskill (Doing Good Better) and Peter Singer (The Most Good You Can Do), questionable thinkers like Nick Bostrom, despicable billionaires like Elon Musk, and—to crown it all—disgraced crypto-entrepreneur Sam Bankman-Fried.

From the public eye perspective, EA has been hit by a remarkable number of controversies, given how young it is. The gigantic fraud perpetrated by the just mentioned crypto-currencies mogul Sam Bankman-Fried at FTX certainly didn’t help. But there have also been accusations of a culture of sexual harassment grooming young women for polyamorous relationships. Of course, these issues point to the flaws of individuals or local cultures (like Silicon Valley’s), not to the value of the ideas underlying EA. Still, if you were not suspicious of the Catholic Church given systemic instances of child sexual you’d be a fool.

So let’s go back to the ideas. EA’s emphasis is on impartiality and considerations of global equity, which, again, at first sight sounds pretty unobjectionably good. As Peter Singer—a colleague who I highly respect, incidentally—put it: “It makes no moral difference whether the person I can help is a neighbor’s child ten yards away from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away. ... The moral point of view requires us to look beyond the interests of our own society.” [4]

The moral point of view? As far as I can tell there is no such thing as a singular, well defined, universal moral point of view. Morality, for me, is a cultural outgrowth of our natural instincts for cooperation and reciprocity that evolved to facilitate life in a social species. Which means that one could just as reasonably argue that of course I have special duties toward people near me, including my neighbor, on the grounds that their wellbeing and happiness depend more directly on my behavior. Much more directly than it is the case for Singer’s child in Bengal. Which is not to say that in absolute terms my family is more important than the Bengali child. But why think in absolute terms, given that ethics is the way we answer first and foremost the local problems of co-existence with our fellow human beings?

[Wait a minute, I hear some of my readers object, aren’t you a Stoic? Aren’t Stoics cosmopolitan? Yes, but as Marcus Aurelius put it: “As Antoninus, my social community and my country is Rome, but as a human being it’s the universe. So it’s only things that benefit these communities that are good for me.” (Meditations, 6.44) This suggests that a Stoic can have multiple simultaneous duties and allegiances. The cosmopolis is the always present background, not the foreground. Perhaps I should write a separate essay about this.]

Singer is also famous for the so-called drowning child thought experiment: if you were gingerly walking about on a nice day, sporting your recently bought very expensive Italian suit and suddenly saw a child drowning in a nearby river, would you ruin your suit in order to save him? Singer is betting that the non psychopaths among us would respond, “obviously yes!” But the thought experiment can be criticized on other grounds. For instance, philosopher (and cosmopolitan!) Kwame Anthony Appiah has answered that—according to utilitarian logic—instead of ruining his suit to save a drowning child he should sell the suit and give the money to charity, even at the cost of the child actually drowning [5].

Speaking of saving children—an ever popular subject matter among moral philosophers—during a debate in 2015, EA advocate William MacAskill was asked whether he would save a child from a burning building or save a Picasso from the same building and sell it for charity. He said the latter, thereby agreeing, perhaps unwittingly, with Appiah’s criticism. Then again, MacAskill has also argued that the worst kind of elitism is donating to art galleries and museums rather than charities. But isn’t art one of the things that makes human life bearable, and hence saving the child worthwhile? This is another way of looking at the repugnant conclusion: in a utilitarian world there would be no “superfluous” stuff like art, music, literature, because one could not make a moral argument in favor of allocating any resources to that sort of stuff (let alone sports and leisure!) rather than toward ameliorating the conditions of an endless and ever increasing number of barely non-miserable human beings.

[William MacAskill, one of the engines behind the EA movement. Image from Wikipedia, CC license.]

(Incidentally, some EA types, like my former Rationally Speaking podcast co-host Julia Galef, advocate for as much reproduction as possible—even in an already overpopulated and environmentally taxed planet. Why? Because that way the chances that we’ll see another Einstein appear on the scene go up, thus increasing the likelihood of more scientific and technological progress. Hmm…)

You may have noticed that a large component of EA’s approach is based on counterfactual reasoning: how much good could you do if you dropped your plans for life and career and chose instead to maximize financial gains so you could donate to charity? The problem with counterfactual reasoning, though, is that it’s next to impossible to test it empirically, so that we are reduced to go for evocative imagery and artificial scenarios (often featuring drowning or burning children, for some reason), perhaps not the best way to make one’s lifelong decisions.

It’s not that EA lacks action-guiding criteria. If anything, there may be too many, and some of them may be in tension with the others. Some EA advocates include the wellbeing of animals among their objectives, others add future human beings (so-called longtermism). But both such extensions of course come at a price: on a world of finite resources anything we devote to the wellbeing of animals or of not yet existing humans is something that is subtracted from the quest for wellbeing of currently living humans. And is it really true that we have moral duties toward future members of our species? How far into the future, exactly? How are these duties to be balanced with the urgent demands of the here and now?

Generally speaking, EA criteria for action include: (i) importance, (ii) tractability, and (iii) neglectedness. Which means EA supporters, ideally, would take into account how important a particular need is, how tractable the problems posed by the satisfaction of said need, and whether that issue has so far been neglected. Okay, but “importance” is a pretty vague and subjective concept. What may be important to me is perhaps irrelevant to you. In an attempt to objectify and quantify the issue, EA proponents have argued that we should introduce another criterion: the estimated number of quality-adjusted life years (QALY) per dollar spent. Critic Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry (a research analyst at the Ethics & Public Policy Center), however, has warned of what he calls the measurement problem, i.e., the difficulty of coming up with reliable quantitative estimates when it comes to either complex problems or long-term scenarios, or both.

For example: EA members Michael Kremer and Rachel Glennerster (both University of Chicago economists) carried out a series of randomized control trials to determine which intervention more effectively improved children test scores in Kenya. Good, I’m all in favor of rigorous scientific and quantitative approaches to a problem. The result showed that the desired outcome did not depend on, say, the availability of new textbooks, or smaller class sizes. Improvements resulted from medication to get read of intestinal worms. Clearly, that solution applies to that particular population in that specific environment. I sincerely doubt that deworming children in New York City or London would have the same effect. In those cases probably small class sizes would achieve a better result. And to complicate things further, a number of other studies have found that deworming programs are actually not effective in the long term. That’s a measure of the divide between theory and reality.

Perhaps the broadest and most damning criticism of Effective Altruism is that it does not address the structural problems that create the sort of injustice and inequality the movement is concerned with. Indeed, it makes them worse by using billionaires as a source of funding and by attempting to convince even more people to go into the sort of high earning careers that exacerbate inequality, environmental damage, or both [6,7,8,9].

I think it’s fair to see Effective Altruism as a range of ethical positions ranging from the minimalist one—that if you wish to donate to charity you should do some research and make sure they are effective—to the most philosophically speculative—that we should adopt a utilitarian philosophy and concern ourselves with the wellbeing of humans in the distant future while doing away with “luxuries” like art and literature. I’m good with the minimalist position, but increasingly uncomfortable as we move toward the more philosophically speculative end of the spectrum.

For me, though, the most problematic point of it all is the one I raised early on: I think the whole of modern moral philosophy is profoundly misguided, and it has been since the Enlightenment and its immediate aftermath, when first Kant and then Bentham and Mill made the two spectacularly and influential wrong turns that have given us deontology and consequentialism. I am, not surprisingly at this point, for a return to virtue ethics, which would not so much disagree with EA as recast the whole discussion within a completely different framework based on elements like role ethics and character development instead of quantification, universalization, and dubious thought experiments.

_____

[1] MacAskill, William, “Effective altruism: introduction.” Essays in Philosophy 18(1):eP1580:1–5, 2017.

[2] Parfit, Derek, Reasons and Persons, Clarendon Press, 1984, p. 388.

[3] As my colleague Richard Chappell has pointed out, my discussion of utilitarianism and the repugnant conclusion actually applies to a more recent theory in contemporary ethics, known as “totalism.” The subject is complex and unresolved, part of the general field of population ethics.

[4] Singer, P., “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” Philosophy & Public Affairs 1(3):231-232, 1972.

[5] Appiah, Kwame Anthony (2006). Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, W.W. Norton & Co., pp. 158–162.

[6] Lichtenberg, Judith, “Peter Singer’s Extremely Altruistic Heirs,” The New Republic, 30 November 2015.

[7] Srinivasan, Amia, “Stop the Robot Apocalypse,” London Review of Books, 37(18), 24 September 2018.

[8] Earle, Sam and Read, Rupert, “Why ‘Effective Altruism’ is ineffective: the case of refugees,” Ecologist, 5 April 2016.

[9] Táíwò, Olúfẹ́mi and Stein, Joshua, “Is the effective altruism movement in trouble?,” The Guardian, 16 November 2022.

Massimo, I’ve long been a fan (I used to regularly attend your meetups at Society for Ethical Culture when I lived in New York) and I thoroughly enjoyed the book you edited called “How to live a good life,” which presented 15 different perspectives/philosophies on how to answer the title question. Given that one of the essays was dedicated to Effective Altruism, it left the impression that, though you wouldn’t endorse the full program (you wrote the essay on Stoicism, after all), you did find enough of its ideas worthy enough for consideration, at least insofar as one is working out their own philosophy of life.

This is where I land. Is the dominant ethical framework behind EA (consequentialism) logically sound? No, but neither is virtue ethics. Neither is, well, any ethical framework, but we needn’t set the bar so high. In my view, what’s important is that both consequentialism and virtue ethics make valuable contributions to the question of how we should live our lives. I’d argue we don’t need to lose sleep over taking any of them to their logical extremes because that’s never going to happen anyway. Hopefully I’m not raising your ‘No True Scotsman’ hairs by mentioning Stoicism and EA in the same breath, but they’ve both lent valuable insights to how I launch the arrow.

I share your critique that, to put it slightly differently, the existence of charity is itself proof that the underlying system is deeply flawed. Indeed, if it were working well, there wouldn’t be any need for charity (at least not on the scale at which it exists today). However, I don’t think this fact is sufficient to then conclude that neither I nor other privileged (i.e. not rich, but middle-income members of high-income nations) individuals should not give to charity or that we should disregard the whole enterprise. (To be fair, you didn’t outright say this, and indeed you mentioned you yourself give to charities you think are plausibly good, but the overall effect of your post’s charity skepticism could well come off as a prescription for what people should, or in this case, should not do. And this worries me. More on this soon.)

I think it’s important to distinguish between descriptive claims about the whole and prescriptive claims for individuals. On the whole, it’s unfortunate we need to have charity, but that’s the world we currently inhabit. I’m sure you’ve seen ads from nonprofits saying “take my job away.” And surely, the aim of The Against Malaria Foundation is to one day close its doors. Similarly, environmentalists are sometimes derided as hypocrites for flying in planes, but they too have to live in the world they’re trying to change. True, it would be better to wave a wand and have progressive taxation in the US (where I live), but while I continue to advocate for that, I also focus on what’s more within my control, and that’s charitable donations to effective charities, at 10% of my income. And doing so does not preclude one also maintaining a Stoic practice, volunteering locally, doing direct work, and voting.

I worry that the (otherwise very healthy) conversation about charity skepticism more broadly and the more narrow critiques of how EA in particular thinks about charity ultimately end up convincing people not to give anything. That would be a real shame. Especially if the reasons for quitting are ultimately due to unrealistic standards or the inability to live with the discomforts of ambiguity.

One thing I like about EA is it itself sprung out of charity skepticism and it ultimately worked to provide surer bets on where charity can do a ton of good, particularly in terms of global health and wellbeing.. And then of course it evolved and began to tackle other noble pursuits. Are there trade-offs between animal welfare and human welfare? Do we have an obligation to people alive 1000 years from now? Can you really use units like QALY as an imperfect but useful measure to compare charities? I don’t see these questions as hits against EA. These conversations are the lifeblood of EA. Did WIll MacAskill really advocate for taking the painting over the child in the burning building? In a way, who cares? EA is not a church and Will is not its priest. It’s not a monolith, and as movements go, I can’t think of another with greater viewpoint diversity than EA.

Finally, you mentioned that EA has had unfortunate subscribers -- people like SBF and Elon Musk. But this isn’t a reason to discard the underlying philosophy -- after all, Stoicism counts Jeff Bezos among its ranks, along with plenty of tech bros. And on the concept of thought experiments -- Epictetus likened the death of a child to losing one’s favorite cup. The point is it’s not hard to cherry pick the eye raising stuff in any body of literature. What matters is if the sensational bits are indicative of something rotten within. In the case of both EA and Stoicism, assuredly no. And indeed I don’t think these lines of argument follow in the spirit of steelmanning.

Perhaps I’m a walking contradiction or maybe I’m just hedging my bets, but I’m someone who has been heavily influenced by both Stoicism and EA. I see each of their strengths and limitations and, yes, some inherent tension between, but I have fairly high confidence that how I’m living my life and the mark I’m able to leave on the world is much greater thanks to their positive influences.

I kinda like Less Wrong!

But I'm also semi-nuts, so touché, good sir.