Should academics be political activists?

Navigating the perilous waters of public intellectualism

Something has been bothering me for some time now. And one good use of writing is to tackle issues one is not clear about, because we are forced to read more carefully in order to write as clearly as possible. Clear writing only comes from clear thinking. So here it goes.

The issue in question is whether academics should also be political activists. If you think the answer is straightforward, I hope you will think again. It is not.

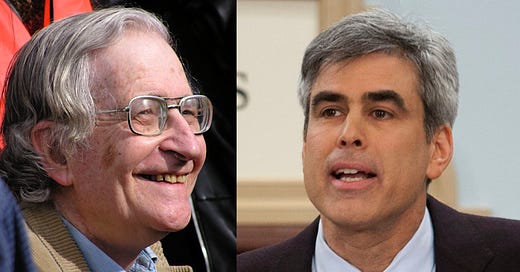

So here is the plan. Let me begin with a concrete example at my own university, proceed by picking two champions of opposing views—Noam Chomsky and Jonathan Haidt—continue with a personal instance from my own teaching and writing, and then see if we can make way on the whole shebang.

An example: land acknowledgment statements

As we all know, the United States of America began its history with a large dose of Enlightenment ideals (Franklin, Jefferson, and the other “founding fathers”), religious fundamentalism (Puritans), slavery, and genocide. The latter issue is the reason for increasingly common “land acknowledgment statements” made by universities and other institutions at the beginning of official meetings and events. The City College of New York, where I work, has adopted the following one:

“We acknowledge that The City College of New York, grounded on the schist bedrock outcrop of Harlem, is situated upon the ancestral homeland and territory of the Munsee Lenape, Wappinger, and Wiechquaesgeck peoples. As members of an educational community, we are obligated to know the histories of dispossession that have allowed the City College of New York to grow and thrive on this vibrant terrain. As designers and thinkers, we endeavor to build in ways that lead toward justice, and we are committed to working to dismantle the ongoing consequences of settler colonialism and to restore the whole people to the full enjoyment of their rights and heritage.”

Setting aside the detail that Wiechquaesgeck appears to be misspelled (it should be Wecquaesgeek), I agree with the general sentiment. Injustice ought to be recognized and addressed. But is the City College of New York actually “working to dismantle the ongoing consequences of settler colonialism and to restore the whole people to the full enjoyment of their rights and heritage”? I don’t see much evidence of it. Nor would I expect it, because the primary missions of a university are scholarship (research, in STEM fields) and teaching, not dismantling the consequences of colonialism and restoring people’s heritage.

Arguments have been made—by colleagues who have thought about this stuff—that reading such statement in public sends a bit of a chilling and counter-educational message to faculty and students, because it strongly implies that anyone disagreeing, for whatever reason, with the statement is not welcome on campus. It also implies that group thinking is encouraged, which most definitely it should not. Finally, this sort of thing can fairly be criticized as virtue signaling, given that it doesn’t actually accomplish anything practical on behalf of the people about whom we are allegedly so concerned.

Okay, mull this over and set it aside, for now.

Chomsky: the duty of a public intellectual

On 23 February 1967, in the midst of the Vietnam War, linguist Noam Chomsky published a landmark essay entitled “The responsibility of intellectuals.” It builds on a series of articles published twenty years earlier by American writer, philosopher, and activist Dwight Macdonald, which Chomsky had read as an undergraduate student. The beginning of Chomsky’s essay goes like this, in part:

“With respect to the responsibility of intellectuals, there are still other, equally disturbing questions. Intellectuals are in a position to expose the lies of governments, to analyze actions according to their causes and motives and often hidden intentions. In the Western world, at least, they have the power that comes from political liberty, from access to information and freedom of expression. For a privileged minority, Western democracy provides the leisure, the facilities, and the training to seek the truth lying hidden behind the veil of distortion and misrepresentation, ideology and class interest, through which the events of current history are presented to us. The responsibilities of intellectuals, then, are much deeper than what Macdonald calls the ‘responsibility of people,’ given the unique privileges that intellectuals enjoy.”

I have always thought—and still think—this passage to be one of the most powerful that I have ever come across, in any writing. I think of myself, perhaps immodestly, as a public intellectual, though not of the caliber of Macdonald or Chomsky. I do live in a western democracy (of sorts), and I do have the kind of access to information, political liberty, and freedom of expression that make it possible for me to speak or write about whatever I want. Such privileges, to me, imply the corresponding duty of making a good use of them, which means actually speaking or writing about social and political issues that i think are important and about which I may have something original or at least competent to say. (More on the latter point below.)

Case closed, then, right? Not quite.

Haidt: scholarship is incompatible with activism

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt takes, in a sense, the opposite position to the one advocated by Chomsky. Check, for instance, an article he published at his “Heterodox Academy” site, entitled “Why universities must choose one telos: truth or social justice.”

A “telos” is a goal, or purpose, a concept famously articulated by Aristotle over two millennia ago. For instance, the telos of a doctor is to cure people, while the telos of a bread knife is to cut bread. What, asks Haidt, is the telos of a university? He writes:

“The most obvious answer is ‘truth’ — the word appears on so many university crests. But increasingly, many of America’s top universities are embracing social justice as their telos, or as a second and equal telos. But can any institution or profession have two teloses (or teloi)? What happens if they conflict?”

Good question. And we have all seen instances of conflict, at the local as well as national levels, over the past several years. Just one personal anecdote among many: I once visited a class taught by a colleague (not in my Department) who was teaching about feminist and gender issues. The topic is, of course, perfectly legitimate, if potentially politically controversial. At one point one of the students asked about the possibility of biological differences between sexes (not genders). The faculty responded that they would not consider such “nonsense” during that course, focusing instead on social justice.

As a biologist I was taken aback: biology is most definitely not irrelevant nonsense when it comes to differences between sexes (the jury and empirical evidence is way out there still concerning genders). I hope we can all agree, for instance, that anatomically speaking it very much makes a difference whether an individual carries two X-chromosomes or one X and one Y. And anatomical differences do have at least potential implications in terms of an individual’s psychology, and therefore in terms of social interactions.

My colleague spectacularly missed a golden teaching opportunity: instead of coldly dismissing the student (never good pedagogical practice!) they could have taken some time to explore the issue, perhaps eventually bringing up a distinction between biological facts and moral or legal rights. Instead, a chilling and decidedly anti-critical thinking message was clearly and sharply delivered. Too bad, really.

A personal example: science vs pseudoscience

Okay, so I’m sympathetic to both Chomsky and Haidt. Let’s see how this apparently contradictory stance plays in my own classroom.

From time to time, at City College, I teach a version of our philosophy of science course that deals with what is known as the demarcation problem, i.e., the differences between sciences and pseudosciences. I’m fairly qualified to do so, as I have co-edited an academic volume on the topic, authored several technical papers, and written a book for the general public. (I also write regularly on similar issues for Skeptical Inquirer magazine.)

Already here you can see a potential problem: writing for Skeptical Inquirer can certainly be construed as public advocacy, since it is a magazine that aims at combating pseudoscience. Indeed, the very term pseudo-science is never meant as a compliment, or even neutrally, as “pseudo” means fake in Greek. So how can I in good conscience teach about the demarcation problem while at the same time I’m advocating against pseudoscience? How is that different from my above mentioned colleague who advocates for sex- and gender-based rights in the classroom and is not even willing to entertain the possibility of biological effects on either sex or gender?

And it gets worse. Some of my favorite examples of pseudoscience, which I discuss at length with my students, are what I refer to as climate change and vaccine denialism. I don’t use the more neutral label of “skepticism.” I talk about denialism. Moreover, as we all know, these are extremely politically charged topics, as one of the two major parties in the United States right now—as well as a number of similar parties in European countries—have made it part and parcel of their platforms to reject the existence of climate change and to brand vaccines as dangerous and unsafe.

How the hell am I supposed to navigate this sort of quagmire?

The twin solutions: facts vs values, institutions vs individuals

I think a reasonable solution, not just for me but in general, is to keep in mind two important distinctions: (i) between facts and values; and (ii) between the roles of individuals and the institutions in which they happen to work.

Let’s start with the first one. Values are not facts, though they should, whenever possible, be informed by facts. Ethics is not a science, it is a branch of philosophy. While it is dangerous to do ethics regardless of factual knowledge of the world, the latter by itself does not determine our values.

Take, for instance, the right to die issue. I happen to think that we should have such right, that is, that someone who is terminally ill, suffers incurable and hard to endure pain, and so forth, ought to have the option of voluntary euthanasia, ideally assisted by a physician, not only to make sure they do it properly, but so that they can do it all, if they happen to be physically impaired.

But I understand the objections to my stance, which vary from principled ones (life is sacred, given by God, etc.) to the practical ones (how do we make sure there aren’t any abuses?). Because of this, I do not advocate for the right to die in my classroom, though I may cover the issue in a class on ethics or introductory philosophy, providing my students with informative materials so that they can properly assess the pros and cons. However, outside the classroom I most definitely do advocate for such right, donate money to elected officials who have endorsed it, vote for them, and even campaign against or otherwise pressuring those who have not.

General lesson: facts and values are conceptually distinct, though sometimes practically intertwined. So it is possible to teach the facts while acting on one’s values outside the classroom.

Second, institutions vs individuals. You may have noticed this already, but Chomsky is talking about the duties of public intellectuals, not of the universities or other organizations in which such individuals happen to work. In a complementary manner, Haidt objects to institutional endorsement of politically controversial positions, not to the notion that individual faculty or students may do so.

And herein lies another important distinction that is helpful in navigating these treacherous waters. For instance, I have my own opinions about the war in Ukraine, or the Israeli-Palestinian conflicts. Such opinions have no place in the classroom, but I most certainly feel free to articulate them outside of work.

But, you may object, if you engage in public advocacy, even outside the school setting, your students are bound to find out, and isn’t that just as bad? No, I don’t think so. We all have opinions, and it is undesirable for scholars, or journalists, or whatever, to pretend they didn’t. That would be deception, not a positive value in my book. On the contrary, if a student is motivated enough to spend some time researching my opinions about things we haven’t discussed in class, good for them. We can always talk about them—after the course is over.

General lesson: there is no contradiction between teaching in a classroom and advocating in the public square. There is, however, a contradiction in carrying out both activities within a school setting.

Finally, let’s apply the above considerations to my specific conundrum about science vs pseudoscience. The way I see it—hopefully rationally, rather than rationalizing—is that when I tell my students that climate change denialism is just that, and not a form of critical thinking, I’m following the facts as best as a scientist and philosopher can. When I argue on behalf of action to properly deal with climate change outside of the classroom, however, I am indeed doing activism. But that’s legitimate because it is not coercing or pressuring any of my students.

Moreover, I make a point, when discussing the demarcation problem in class, to highlight that while some notions appear to be clearly pseudoscientific, others are borderline, and the jury on the latter ones is still out. Borderline fields include parapsychology and evolutionary psychology, in my opinion, possibly even certain ways of doing economics, and definitely some approaches to psychology and sociology. And there is always the possibility—as remote as it may now seem—that something we consider a clear example of pseudoscience (say, astrology) will turn out to mature into a scientifically respectful endeavor. Historically, I can’t think of a single example of that ever happening, but I do have a number of examples of once accepted sciences that eventually slid into the realm of pseudoscience (e.g., alchemy).

I recognize, however, that this is treacherous territory, and that I can easily slip into a sarcastic or dismissive tone if I don’t watch myself. Avoiding such peril is one of the hallmarks of a good teacher. And I flatter myself to think that I belong in that category. It is, therefore, possible to successfully navigate the Scylla and Charybdis outlined by Chomsky and Haidt. But one needs to be careful in doing so: Odysseus famously lost all several members of his remaining crew in accomplishing just such feat. He did get to Ithaca, though…

Your discussion Of the individual academic's role seems clear enough. To take an example from my classroom, I taught about radiometric dating. It would not have been appropriate for me to point out that The results I quoted were incompatible with Young Earth creationist religion, although when I was teaching in Texas I feel sure that some of my students made this inference without my help. Much more difficult is the role of the institution. An institution has power, and its actions have consequences. Should it, for example, offer free tuition to people who can show membership of dispossessed tribes? And how should it invest? Tobacco shares, fossil fuel shares, armaments, companies based in Israel, or in China?

Thanks for this Massimo! We're navigating a new level of strain on the intersection of politics and academia here in Florida - its been building for some years now, before the current administration. After George Floyd's murder, we were working diligently to consider social injustices in our field (as were many around the country): evolutionary biology having a particularly unsavory past as you know. Looking back, we played our part in what Christopher Rufo understood as the growing momentum of DEI. He then developed a very strategic (and obviously successful) attack on the movement. I still hold out with some of this restructure/ and teaching of some of the relevant history in my evolution class. Its a risky business but I stick to the facts and rely on Joseph Graves recent article https://doi.org/10.1525/abt.2023.85.3.133.

I came back to this post today in prep for our Stand up for Science rally. Also taking courage from your previous post as I try to figure out what I can do: "Seneca talks about expanding or contracting ourselves in response to external conditions, meaning we should adapt to the situation: If we can do a lot, we should, but if we can only do a little, that’s no excuse for doing nothing. So, reexamine your own life through Seneca’s lens, and see where you can act effectively to make the world even a little bit better. It’s the virtuous thing to do."