Protagoras: should we re-evaluate the Sophists?

Perhaps Plato was a bit too harsh

I have always been fascinated by the Presocratics, the very first philosophers of the Western tradition. They were the ones that began those two great enterprises of the human intellect that we today refer to as science and philosophy. They wanted to know how the world works and what our place in it happens to be.

So it has been with great interest that I read the excellent The First Philosophers: The Presocratics and the Sophists, by Robin Waterfield (Oxford University Press). Robin, incidentally, is rapidly becoming one of my favorite translators and authors. Check out his versions of Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, and Plutarch. Not to mention his recently released biography of Plato.

But, wait, the Sophists? As anyone who has cut his philosophical teeth on Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, I don’t tend to have a good opinion of the Sophists, and I have indeed explicitly used the term as one of abuse to recount a particularly distasteful encounter I’ve had with a friend of a friend.

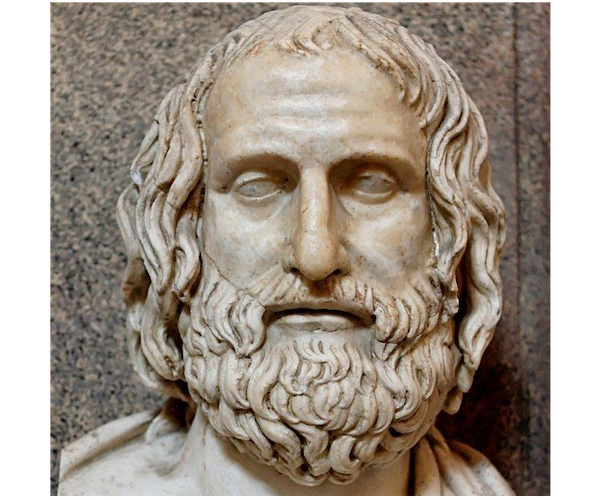

While Waterfield’s book in part confirms my attitude toward the Sophists, it also goes a long way to correct it and make it more nuanced, particularly when it comes to one of the most famous thinkers who falls under that label: Protagoras of Abdera, the first Sophist to be discussed by Waterfield in the second section of his book.

Born in Abdera, in northern Greece, Protagoras found fame in Athens, where he became part of the inner circle of the influential statesman Pericles. He was the founder of the Sophistic movement, famous even in antiquity for the concept that man is the measure of all things, which Waterfield—correctly, in my mind—takes to be not an expression of epistemic relativism, but rather an articulation of the humanistic and democratic tendencies of the whole movement.

Man is the measure of all things—of the things that are, that they are, and of the things that are not, that they are not. (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, IX.51–3)

There is no question that Protagoras’ approach to debate was somewhat shady from an ethical perspective, though we don’t have to buy wholesale the extremely negative characterization we get of both him and the Sophists more generally from Plato. After all, being able to argue different sides of a given thesis is a good way to understand the various positions at play in a more objective fashion—which of course didn’t stop others from making fun of Protagoras, whether in Aristophanes’ Clouds or in Aristotle’s Rhetoric.

The Sophists claimed to teach arete, i.e., excellence in general, and Protagoras in particular taught the art of political success. He actually said that he was teaching people how to be good citizens, though as Waterfield points out, this needs to be tempered by the fact that his fees were rather exorbitant, effectively pricing out most Athenians:

These are good questions, Socrates, and I enjoy answering those who ask good questions. If Hippocrates comes to me, he won’t experience what he would if he went to any of the other Sophists. I mean, the others all treat young men in a disgraceful fashion. They take people who have shunned the arts and crafts, turn them around again against their will, and get them involved in arts and crafts, by teaching them mathematics and astronomy, geometry and music—here he glanced at Hippias—whereas if he comes to me he will learn exactly what he came to learn. What I teach is the art of making good decisions, both in one’s domestic affairs, so that one can manage his estate and household in the best possible way, and in the affairs of the community, so that he can maximize his potential to conduct political business and address political issues. (Plato, Protagoras, 316–319)

There certainly are positive features in Protagoras’ program, particularly the notion that civic virtue is teachable, the rather radical idea that justice should not be retributive, and an emphasis—arguably for the first time in history—on the fact that rational discourse should play a prevalent role in the conduct of the affairs of the state.

That said, the sort of society envisaged by Protagoras was democratic yet not egalitarian, since he recognized the existence of expertise in both morality and politics. This is an interesting point that is still controversial today, even though it appears to me to be obviously true.

Protagoras—and the Sophists more generally—were closely involved in a major debate of the time, pitting the value of nomos (i.e., human law or convention) versus that of physis (i.e., natural law). A classic Protagorean example is the wind: it makes no sense, for Protagoras, to say that the wind is intrinsically cold. Rather, it feels cold to certain people under certain circumstances, it is a matter of nomos, not physis.

If Protagoras was a “relativist” he was a rather sophisticated one, not prone to violate the basic laws of logic. For instance, to say that the wind is cold for me at this time and yet that it may not be cold for someone else at this same time, or for me at another time, does not violate the law of non-contradiction: “W is C for M at time t” does not contradict “W is H for M at time t+1.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Figs in Winter: a Community of Reason to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.