I have recently written three essays about Odysseus as interpreted philosophically by the Cynics, the Stoics, and the Epicureans, a reflection of my interest in the idea of Stoic role models, as well as my personal passion for the cunning Greek hero.

While those three entries were based on a highly recommended book by Silvia Montiglio (which also covers Platonism), this last entry in my little tetralogy moves forward about a millennium, to see how the great Italian poet Dante Alighieri treats Ulysses (as he was known by the Romans) in Inferno 26, one of the most beautiful passages in the Divine Comedy. This will also give us a chance to look at the surprisingly similar way in which Seneca treats Ulysses, from a Stoic perspective.

My main source for this essay is a scholarly article by Gabriel Pihas, published in 2003 in Dante Studies, the Annual Report of the Dante Society, and entitled “Dante’s Ulysses: Stoic and Scholastic models of the literary reader’s curiosity and Inferno 26.”

Ulysses is an important figure in Dante’s Comedy. To begin with, he is the only ancient mythological character that has a major role, all the other main figures being historical individuals, and usually Dante’s own contemporaries. More importantly, Ulysses plays the part of Dante’s consciousness in the poet’s version of a debate that began with Aristotle’s Poetics, continued with Seneca’s discussion of literary studies in his letter on curiosity to Lucilius (LXXXVIII, On Liberal and Vocational Studies), and characterized an important phase of Scholasticism near the end of the Middle Ages, when Thomas Aquinas was seen as a dangerous, possibly heretical, exponent of a new way of doing things.

The fundamental opposition in Canto 26 of Inferno is between curiosity for curiosity’s sake, and curiosity for things that are morally relevant, what Aquinas referred to respectively as “curiositas” and “studiositas.” As Pihas puts it: “In Inferno 26, curiosity is fundamentally understood, following Seneca, as a problem of the seduction of language and rhetoric, both in philosophic disputation and in poetry. Calling curiosity into question [via his dialogue with Ulysses] is Dante’s form of literary-philosophical self-consciousness.”

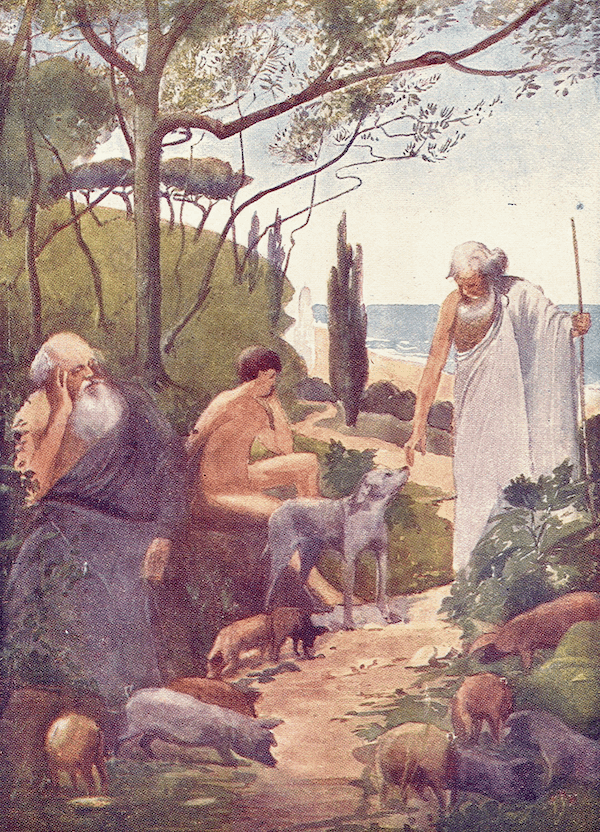

At the beginning of 26, Dante almost falls into the pit where Ulysses is being punished, because of his irrepressible interest in the fate of the Greek hero. This is usually interpreted as a metaphor to remind the reader of Ulysses’ own downfall, brought about by his curiosity about the world. In the version of the story that Dante relates, Ulysses left Ithaca again, after his return home and the punishment of the suitors. He headed toward Hercules’ Pillars (the Strait of Gibraltar), intent on navigating the open ocean to see what lies beyond. And he and his crew perished during the ambitious attempt.

Pihas points out that Seneca’s letter mentioned above is the inspiration for Dante’s encounter with Ulysses, and possibly even for the famous opening lines of the Comedy itself, which find Dante lost in the middle of a forest, a metaphor for what we would today call his midlife crisis, and which is the trigger for his journey of spiritual rediscovery:

In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to myself, in a dark wood, where the direct way was lost. It is a hard thing to speak of, how wild, harsh and impenetrable that wood was, so that thinking of it recreates the fear. It is scarcely less bitter than death: but, in order to tell of the good that I found there, I must tell of the other things I saw there. (Inferno, Canto 1)

Back to Seneca, here is what he writes to Lucilius about Ulysses:

Do you seek out where Ulysses’ wondering took him more than try to end our own perpetual wonderings? We don’t have the leisure to hear whether it was between Italy and Sicily that he ran into a storm, or somewhere outside the sea of the world we know … when everyday our souls are running into our own storms, and driven into all the evils that Ulysses ever knew. We are not spared those beauties or enemies that attract the eyes. We too have to contend in various places with savage monsters rejoicing in human blood, insidious voices that flatter our ears, shipwrecks and all manners of misfortune. What you should be teaching me is how I may attain such a love for my country, my father, and my wife, and keep on course for those ideals even after a shipwreck. (Letter LXXXVIII.7)

Dante, in Inferno 26, is burning from the desire of asking Ulysses precisely the question that Seneca tells Lucilius should not distract us, because it is mere self-serving curiosity: how did Ulysses die?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Figs in Winter: a Community of Reason to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.