I’m skeptical, not afraid, of AI

Rethinking education and integrity in the age of Artificial Intelligence

So-called generative AI (gAI), also known as Large Language Models, has arrived on the stage with the debut of ChatGPT back on 30 November 2022 and is, very obviously, here to stay. The question is what to do about it. I cannot speak for the broad impact of AI across fields and in society at large. Probably nobody can, at this stage, and those who try are likely to be guessing or, worse, bullshitting. But I think I’m competent enough as a scholar, writer, and teacher, to make some hopefully sensible comments limited to those domains.

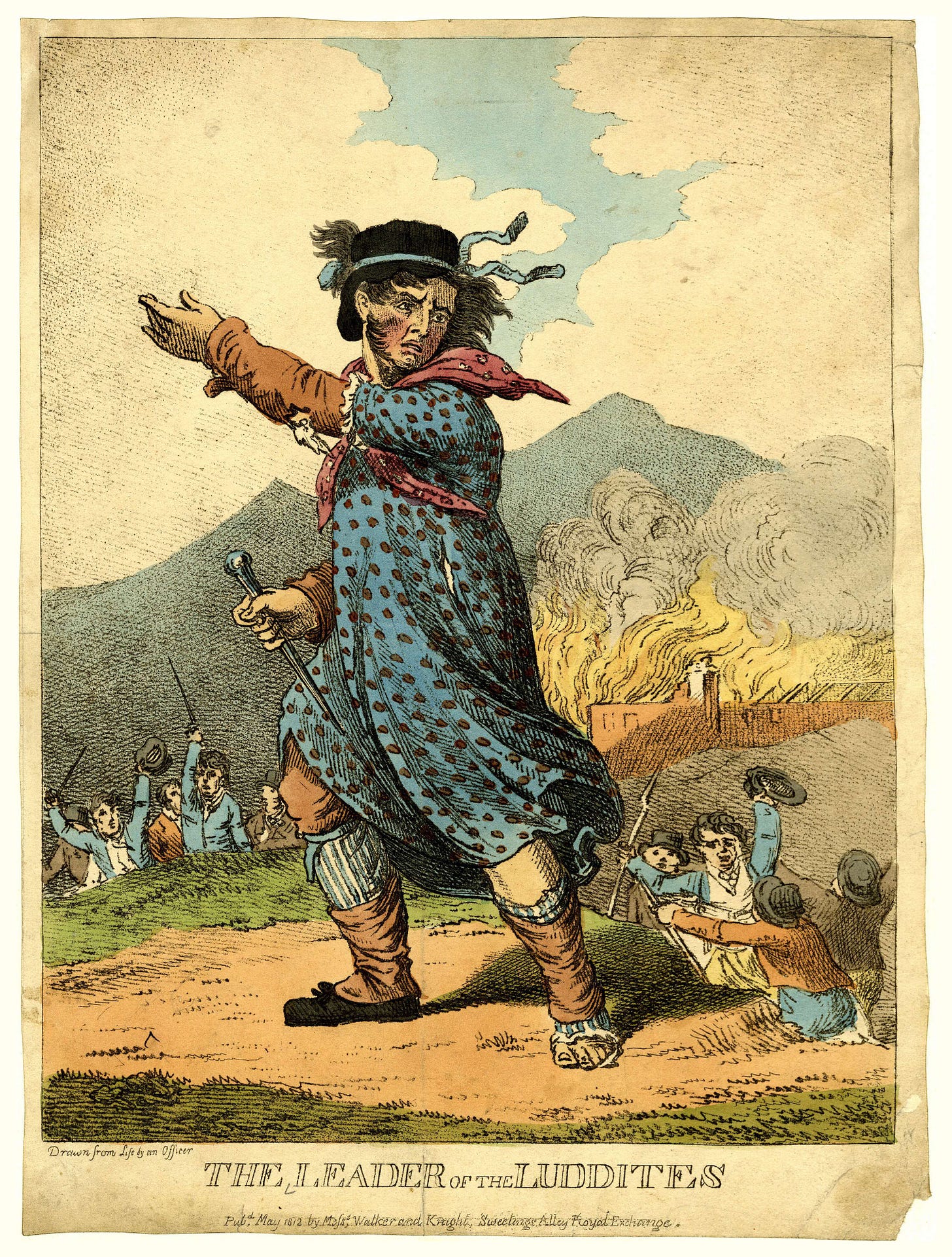

My academic colleagues seem, broadly speaking, to fall into two categories: the enthusiasts and the Luddites. The enthusiasts, as you might imagine, think that gAI is the best thing since sliced bread (which in itself isn’t that good of a thing, anyway) and that we should make every attempt to deeply integrate it in all aspects of our lives and jobs. The Luddites (named after 19th century anti-technologist Ned Ludd), don’t even want to hear the term AI. (To be fair, a probably larger number of colleagues is either entirely uninterested or doesn’t know what to make about all the fuss, waiting for it to settle down one way or another.)

I am most definitely not a Luddite. On the contrary, I’m usually an early adopter of new technology. Then again, I’m also aware of the fact that technology can be used for good or ill, and that even “obviously” good ideas can be turned into really awful ones (see social media, for example). And I’m already on record criticizing the current generation of AI, agreeing with some colleagues in philosophy who consider ChatGPT et similar to be sophisticated bullshit generators (in the technical term of the word “bullshit”). I also sympathize with Noam Chomsky’s notion that gAI is a massive engine for plagiarism.

All of that said, I use gAI on a regular basis. I’m enjoying the slow and careful deployment of Apple Intelligence on my iOS devices; I frequently use Midjourney to produce images that accompany my essays here on Substack; and I make moderate use of Claude to bounce off some ideas and help me track down some familiar references.

What’s the problem, then? It started last year when I took a course on gAI for faculty at the City College of New York. I wanted to learn about the technology and its impact in the classroom and on scholarship, but I quickly tired of the well intentioned fellows who ran the course and who kept telling us not to resist gAI but rather to incorporate it into our teaching. Since they kept being vague about how, exactly, to do that, I asked a simple question: “Could you give me an example?” “Well,” came the response, “you are in philosophy. So perhaps you could task your students to use AI to generate a dialogue in the style of Plato and then ask them to critique it.”

Pause for a minute and consider just how misguided this suggestion actually is. Done? Okay, let’s analyze it a moment. First off, why would I prefer my students to criticize AI-Plato rather than, oh, I don’t know, Plato?? Second, since AI-based plagiarism is a huge problem at the moment, what exactly is going to stop a student from asking ChatGPT to both generate the dialogue and critique it?

I needed something a bit more sophisticated. So I turned to Andreas Matthias, a philosopher (and, before that, computer programmer) at Hong Kong University, who publishes Daily Philosophy on Substack and has written a lot of thoughtful stuff about AI. One of his recent entries, though, entitled “Who’s afraid of AI?” was rather disappointing, and I’m going to use it to highlight our differences while more generally pointing out what, I think, the current problems are with AI and teaching.

Matthias begins with a bit of a detour about one of the latest AI-based technologies: AI glasses. These are devices, being produced for instance by Meta (the parent company of Facebook), which allow the user to interact with an AI while they are looking at their surroundings. This has obvious interesting applications. I may be admiring, say, the Empire State Building and my AI could be projecting all sorts of historical or fun information in front of my eyes, including perhaps a simulation of the construction of the building back in 1930.

Cool. But of course, and much more ominously, AI glasses can also be used to surreptitiously record people and conversations, in and out of the classroom. That is a flagrant invasion of privacy and creates an obvious chilling effect, if teachers or students are aware at all times that they may end up streaming live on YouTube. So the fact that some universities (and, I assume, other places of employment) may be considering banning AI glasses on their premises is not an example of Luddism.

Matthias’s article gets really interesting when he introduces the difference between human and machine expertise. The basic idea, which goes back to the 1980s’ work of philosopher Hubert Dreyfus, is that machines become “experts” at something by accumulating lots of facts and organizing their knowledge base according to lots of rules. At least, that’s how the aptly named “expert systems” of that time worked. Human experts, by contrast, are not just repositories of facts and rules. They constantly reconstruct their understanding of a given area—say, chess—and use it to derive quick, intuitive notions of how to efficiently solve a particular problem within that area. Moreover, a lot of human information is embodied, not encoded. Matthias offers the example of his fast writing on a keyboard: while he obviously hits the keys accurately, if you asked him (or me!) where exactly each key is located he will not be able to answer.

Rules, he concludes, are for novices (and for old fashioned computerized expert systems). Real experts develop a deep, semi-automated competency that doesn’t rely on rules. This is relevant to Matthias’s discussion of AI because he then proceeds to make a distinction, within an educational setting, between skills and knowledge. Examples of skills include playing the piano, piloting a plane, and solving calculus problems. Examples of knowledge include memorizing the periodic table, or recalling Ancient Greek philosophers’ names and theories (e.g., Zeno > Stoicism).

Though there are obviously areas of overlap between skills and knowledge, Matthias contends that the latter is “cheap and easy” because it resembles what computer expert systems of the ‘80s did: an accumulation of rules and facts. From there he launches into an interesting but, I think, inaccurate, explanation of what has happened to higher education in recent times: administrators and faculty have realized that teaching skills is hard and expensive, so they have settled for the transmission of knowledge instead, aiming at making their students into expert systems rather than actual experts.

That’s why, according to Matthias, AI-based cheating is so easy and widespread. As he puts it, “the only thing that universities give to their students, and the only thing they are testing for, is abstract knowledge—and this is exactly what AI, hidden notes, computer files and textbooks contain. … If our students were judged on their ability to actually do something, to perform a skill, to achieve a result, then the use of AI would be welcome as a factor that would support them in that task.”

He continues: “AI is just an interactive textbook, a way of quickly looking up a bit of knowledge; but with a little more time, one could use old Google, or even a library of paper books, to achieve the same result: to look up a piece of factual information. … We have destroyed education, and AI is just making it obvious. The emperor has never had any clothes—but now AI is pointing this out for all to see.”

I disagree. First, it is incorrect, I submit, to claim that all that universities teach their students is theoretical knowledge. When I taught biology I was imparting both theoretical knowledge and laboratory skills so that my students would be able to design and carry out an experiment. My goal in teaching philosophy is for people to learn skills like critical thinking and writing. My colleagues in the Music Department teach their students how to play jazz, which is a skill founded on music theory. And faculty in the Theater Department teach how to put up a play, a skill based on knowledge of plays and of human history and psychology.

Second, although Matthias acknowledges in passing that “the two areas [i.e., theory and skills] overlap,” that acknowledgment is nowhere near enough. Theoretical knowledge and the development of skills go hand in hand and are deeply intertwined, as people have appreciated since the time of Aristotle. There’s simply no doing one without the other.

Third, we most definitely don’t test our students just on their knowledge base. Matthias writes: “I have taught ancient Greek philosophy for decades now—but I still don’t remember the exact year when Plato was born. Why would I? It’s ten seconds away, on my phone, using a simple Google search. There is no point spending mental power on that. Explaining how Plato’s philosophy of love is motivated by his metaphysics of the Forms; or, even better: using Plato’s philosophy of love to explain what’s wrong with today’s dating apps: this is what my skill as a philosophy teacher is about.” But the fact is that I don’t ask my students when Plato was born. They can look that up any time. Instead, I ask them to write papers precisely of the sort that Matthias is talking about.

And therein lies the big rub: gAI is not like a textbook or a Google search, and I’m stunned that a former computer programmer would make that analogy in the first place. Google and books only return facts, they don’t write papers for you. ChatGPT does. It may not do, at the moment, a particularly good job, but it is certainly capable of producing a B-level paper on Plato’s philosophy of love, or even a passable dissertation on how his philosophy explains what’s wrong with dating apps. Don’t believe me? Here’s a sample response from Claude:

“While Plato would likely view modern dating apps with skepticism, his philosophy of love (eros) as developed in the Symposium and Phaedrus offers particular insight into their limitations. For Plato, true love involves ascending from physical attraction toward appreciation of the soul's beauty and ultimately the Form of Beauty itself. Dating apps, by leading with photos and surface-level information, risk trapping users at the lowest rung of Plato’s ‘ladder of love’—mere physical attraction. The algorithmic nature of dating apps also contradicts Plato’s view of love as a form of divine madness (theia mania) that transcends rational calculation. Where Plato saw love as a transformative force that drives us to become better versions of ourselves through philosophical dialogue and mutual growth, dating apps often reduce potential partners to a set of filterable preferences and swipeable images. Most fundamentally, while dating apps promise more efficient matching, they may actually distance us from what Plato saw as love's highest purpose: the shared pursuit of wisdom and understanding that elevates both lovers toward truth and beauty.”

See what I mean? That’s why gAI is a problem, not just for teachers, but for publishers, who since November ‘22 have been inundated with essays, short stories, and whole books “written” by AI. Or for musicians, who risk being replaced by AI-generated music. The issue is not whether one could enjoy literature, philosophy, or art generated by AI. Of course one could. The issue arises when human beings in flesh and blood pretend to pass AI output as their own work and get credit for it. That is called cheating, and it is not acceptable, ethically or otherwise.

I don’t have an answer to these issues. Nobody does. We can’t simply reject gAI because the Pandora box has already been opened, and there’s no putting stuff back into it. But we can’t blame teachers for destroying universities for their own convenience while also accusing them of obtuseness and Luddism. We shall see where all of this goes, sooner rather than later, given the fast pace of AI development. In the meantime, you can rest assured that this essay was written by a human being. Or can you?

If folks are unaware, AI isn't always 'truthful.' They sometimes make things up. See:

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00068-5

Reading the article I can vouch that this was written by none other than yourself as I know your style of writing. You mention that using AI to write a paper could be cheating. If one has an original piece of research data & to save time uses AI to do the analysis & complete the paper as because of time constrains one has in modern times , I think it’s being smart. In the past it would have taken months to complete a paper & what know it takes a weekend. Like social media AI can be of great benefit to mankind if used judiciously. I agree not to be afraid but healthy to be skeptical.