Mantras are sacred utterances common in Eastern traditions such as Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism, Sikhism, and Zoroastrianism. Sometimes these sounds are words that have a semantic content, in other instances they don’t. Mantras are taken to have profound spiritual meaning, and occasionally even magical powers.

Stoics don’t believe in magic, and the word “spiritual” has a very narrow meaning for a philosophy that is rooted in physicalism and causal determinism. Still, Stoicism too has mantras, of a sort. They are always meaningful phrases, meant to be “at hand” whenever a challenge arises for which they may be useful. For instance, if I have a discussion with someone whose ideas are clearly confused or wrongheaded and I see that I’m not making progress by using facts and rational arguments, I will attempt not to be frustrated by repeating to myself “so it seems to him.” If I make a commitment to do something in the future, or be at a particular place at a particular time, I tell myself or my interlocutor “fate permitting,” a reminder that I control my intentions, but not necessarily the outcomes of my actions. And so on.

One of the most famous of Stoics “mantras” was apparently uttered by the second century teacher Epictetus: “ἀνέχου (bear) and ἀπέχου (forbear).” Let’s take a look at what it is about.

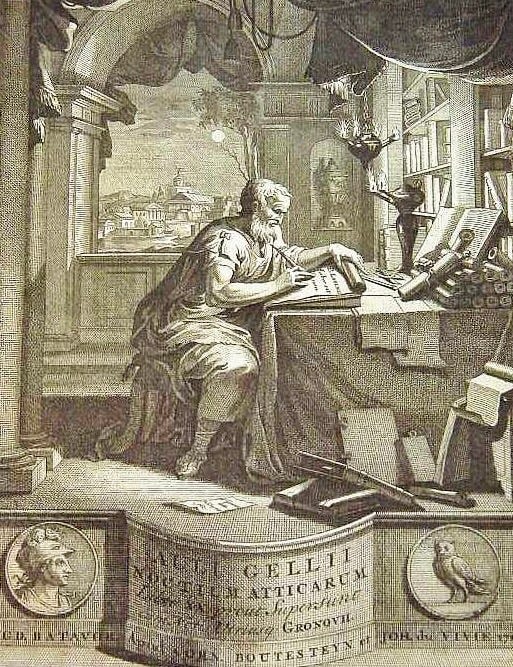

The source for the mantra is Aulus Gellius (125-180 CE), a Roman author and grammarian who wrote Attic Nights, a commonplace book (Adversaria), that is, a collection of personal observations, in the case of Aulus about geometry, grammar, history, philosophy, and other subject matters that interested him. A sort of Substack newsletter ante litteram, if you will. He was a friend of Marcus Cornelius Fronto and Herodes Atticus, both teachers of rhetoric of the future emperor Marcus Aurelius. The title of the book comes from the fact that it was written during an extended stay of the author in Attica, the region of Greece where Athens is located. Attic Nights was likely published in 177 CE, three years before Marcus Aurelius’s death, and is the source of a number of Stoic stories, including the famous one about the pale Stoic in the storm, as well as the one about the logician Chrysippus and his rolling cylinder.

In section 19 of the seventeenth book of Attic Nights, Aulus tells us a story about Epictetus that was recounted to him by the philosopher Favorinus (80-160 CE). The latter was yet another interesting character of the time well worth briefly getting to know. He was a Roman Pyrrhonian Skeptic during the reign of Hadrian and a friend of Plutarch, the above mentioned Fronto and Herodes Atticus, as well as Hadrian himself, among others. That said, Hadrian banned Favorinus—for unknown reasons—in the 130s, though he was rehabilitated by Hadrian’s successor, Antoninus Pius, the adoptive father of Marcus Aurelius. Interestingly, the Athenians, probably to carry favor with Hadrian, pulled down a statue of Favorinus, which led the latter to comment that if only Socrates had had a statue in the city he might have been spared the hemlock.

In Attic Nights, Aulus writes: “I heard Favorinus say that the philosopher Epictetus declared that very many of those who professed to be philosophers were of the kind without deeds, limited to words.” That is, Epictetus was criticizing those people who pretended to be philosophers but didn’t really love wisdom, because they only talked about it, without practicing it.

Arrian of Nicomedia, a student of Epictetus, went into a bit more detail about this in his On the Dissertations of Epictetus, writing that:

“When [Epictetus] perceived that a man without shame, persistent in wickedness, of questionable character, reckless, boastful, and cultivating everything else except his soul—when he saw such a man taking up also the study and pursuit of philosophy and natural history, practicing logic and balancing and investigating many problems of that kind [he would chide him:]: ‘O man, where are you storing these things? Consider whether the vessel be clean. For if you take them into your self-conceit, they are lost; if they are spoiled, they become urine or vinegar or something worse, if possible.’” (Attic Nights, 17.19)

Evidently, Epictetus had no patience for people who studied only in order to impress others and not with the purpose of becoming better human beings. Aulus gives us additional details near the end of section 17.19 of Attic Nights:

“Epictetus, as we also heard from Favorinus, used to say that there were two faults which were by far the worst and most disgusting of all, lack of endurance and lack of self-restraint, when we cannot put up with or bear the wrongs which we ought to endure, or cannot restrain ourselves from actions or pleasures from which we ought to refrain.”

Endurance and self restraint, aimed respectively at putting up with things we ought to bear and at refraining from indulging in things we should not indulge. This sort of talk is likely where the stereotype of Stoicism as a philosophy preaching a stiff upper lip and a life without emotions or pleasure comes from. But such an interpretation misses the mark considering that the Stoics had no problem with pleasure, so long as it doesn’t get in the way of one’s duties toward other human beings. Nor do the Stoics advocate the suppression of emotions, teaching instead to develop a constant dialogue with our feelings, a dialogue aimed at aligning emotions and cognition so that we live a better life characterized by a smooth flow of feeling, thinking, and acting.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Figs in Winter: a Community of Reason to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.